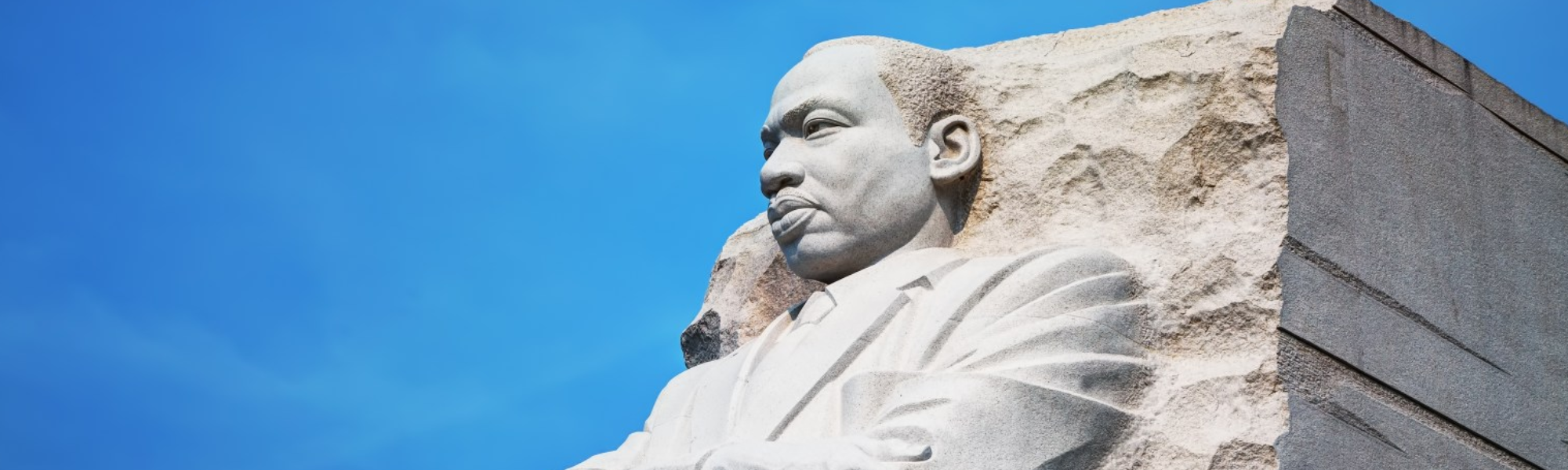

Today, we remember the defining figure of the Civil Rights Era, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. On the fiftieth anniversary of his assassination, leaders and communities across the country are taking the opportunity to reflect on our nation’s history, the progress we’ve made, and how much work we have yet to do.

From Ferguson to Charleston, from St. Paul to Dallas, and now in Sacramento, the televised events of the last few years have served as a horrific reminder of how important it is for cities to acknowledge and take meaningful action on racial injustice. Issuing a press statement after every tragedy or violence is not enough. As Dr. King said, “there comes a time when one must take a position that is neither safe, nor politic, nor popular, but he must take it because conscience tells him it is right.”

In the wake of the 2014 unrest in Ferguson, Missouri, the National League of Cities (NLC) created the Race, Equity And Leadership (REAL) initiative to strengthen local leaders’ knowledge and capacity to eliminate racial disparities, heal racial divisions and build more equitable communities.

In concert with local elected officials and senior municipal staff, REAL is working to explore the deeply-rooted systemic and institutional racism that has created the very conditions we live today. By taking an active role, the initiative is designed to help cities search for solutions to the challenges we face today within an intentional framing of racial equity.

We believe that local government leaders are best positioned to make necessary policy, institutional, and structural changes to reduce disparities and advance equity. Community and nonprofit organizations have an important role, but real progress cannot be made without local government leadership.

As leaders, we must combat the narrative that we live in a post-racial society — and acknowledge that we live in a racialized one.

Today, while still wrestling with these issues some four years after Ferguson, we continue to struggle. Unarmed black men and women are being beaten, tasered and shot to death on camera. Despite these horrific and traumatizing images, or perhaps because some have become numb to them, there doesn’t seem to be an end in sight. Communities are asking: Why?

However, struggles with police-community relations are often only a symptom arising from underlying issues of equity and opportunity for communities of color. In the same way that a doctor observes physical symptoms to diagnose an underlying illness, so must we approach our policies and strategies for racial equity in cities across the country.

We must ask ourselves: What are the causes of today’s symptoms? Policy makers in particular must understand that what we are witnessing today is a culmination of factors within education, housing, economics, health care (physical and mental), policing, criminal justice and others that have led to widespread disparities for people of color.

There is no one single diagnosis — but scores of research gives us insight to a multitude of root causes. When we examine disparities across the country, we know all too well the story that the data tells us: That people of color, especially black men, fare far worse in our country than their white counterparts.

The following are some examples of where we see racial disparities:

- Wealth Gap: In 2016, according to the Pew Research Center, “the median wealth of white households was $171,000. That’s 10 times the wealth of black households ($17,100) – a larger gap than in 2007 – and eight times that of Hispanic households ($20,600), about the same gap as in 2007.”

- Home ownership: According the Harvard State of the Nations Housing Report, “Over the past 12 years, the black homeownership rate fell sharply to just 42.2 percent, slightly below the 1994 level (Figure 4). With white rates increasing to 71.9 percent over this period, the black-white homeownership gap widened by 2.3 percentage points to 29.7 percentage points in 2016—the largest disparity since World War II.”

- Life expectancy: “According to the Center for Disease Control, black mothers in the U.S. die at three to four times the rate of white mothers, one of the widest of all racial disparities in women’s health. Put another way, a black woman is 22 percent more likely to die from heart disease than a white woman, 71 percent more likely to perish from cervical cancer, but 243 percent more likely to die from pregnancy- or childbirth-related causes.”

- Education disparities: In 2017, the Annie E. Casey Foundation used its Race for Results Index to measure how well-being and opportunity are being built and undermined for children of different racial and ethnic backgrounds. They found that Asian and Pacific Islander children have the highest index score, at 783, followed by white children at 713, Latino children, at 429, American Indian children, at 413, and African American children at 369.

For public servants, it should be a primary goal to work to dismantle the institutional and systemic racism that exists in policy. It is especially critical for white persons in positions of authority and power to undo the political foundation of white supremacy — because of the privileged seat they already hold within the system. It is a difficult conversation, but one we must face head on.

As we tell participants in our trainings, “lean into the uncomfortable” — because if it was comfortable, we would already be doing it. Our leaders must also recognize that words are simply not enough. Concrete actions must begin to be set in motion to advance racial equity. Our country has a dark and hurtful history, and it is dismissive and hurtful to merely point to the fact that “Slavery is over.”

In exploring these concepts, leaders working with REAL participate in an exercise called “sticky history”, which highlights a timeline of policies — including redlining, Jim Crow laws, and the Thirteenth Amendment — that led to today’s systemic criminalization of people of color. Exploring the full history, which is often omitted in America’s education curricula, is critical to understand and dismantling racism.

As America’s city leaders tackle the challenges ahead — whether it’s driverless cars, immigration reform, housing, gun safety or others — applying a racial equity lens cannot be optional. These gaps we see are products of gaps created intentionally, so we must be just as intentional about reversing them. People’s lives literally depend on it.

We cannot discuss economic mobility without discussing how policies of the past and today continue to produce outcomes with which, according to Pew, “Among full- and part-time workers in the U.S., blacks in 2015 earned just 75% as much as whites in median hourly earnings and women earned 83% as much as men”.

We cannot discuss justice reform without discussing how policies of the past and today continue to incarcerate black people at 5.1 times that of their white counterparts according to the Sentencing Project. How can we talk about opportunity and wealth when people of color have not been given the same fair opportunity to access these across the history of a lifetime?

To think and talk about race in a vacuum does not create solutions — because people do not live in them.

Cities can move to action by creating space for discussion to action diving into community conversations with the community to unpack the trauma and obstacles that exist. Under the leadership of Mayor Greg Fisher, the City of Louisville, Kentucky, highlighted in one of our eight REAL city profiles, is doing just this by creating a space for residents to openly delve into the city’s fraught history and current issues.

To sustain this work, like in Madison, Wisconsin, policy makers should commit to reversing racially disparate policies by developing racial equity plans — which can provide the city with a purposeful blueprint to applying a racial equity lens to policy and service delivery. Embedding a racial equity lens to how city leaders make decisions moving forward is critical to creating inclusive, thriving and healthy communities that are safe places where people from all racial, ethnic and cultural backgrounds thrive socially, economically, academically and physically.

Fifty years ago, in the last speech of his life, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr, spoke of the parable of the good Samaritan. “The question,” Dr. King said, “is not, ‘If I stop to help this man in need, what will happen to me?’ The question is, ‘If I do not stop to help this man, what will happen to them?’ That’s the question.”

Fifty years later, we still face the same question. So as Dr. King said, “Let us rise up tonight with a greater readiness. Let us stand with a greater determination. And let us move on in these powerful days, these days of challenge, to make America what it ought to be. We have an opportunity to make America a better nation.”

About the Author: Ariel Guerrero is NLC’s REAL Manager, Tactical Support & Outreach Team.

About the Author: Ariel Guerrero is NLC’s REAL Manager, Tactical Support & Outreach Team.