Five years after their introduction as shared vehicles, e-scooters are now in cities around the world. Bird, which pioneered the industry, operates in over 475 cities globally. Shared scooters have become more popular than most foresaw, and research shows they are successfully shifting people out of cars (36% to 49% of rides replace car trips1), reducing harmful emissions and traffic congestion, and boosting local economies.2 All signs point toward more micromobility options ahead.

But how should cities plan for micromobility parking to ensure access while minimizing clutter? The answer begins with planning for people, rather than cars.

Before the car was introduced, the street itself was public space, and not the domain of the automobile. There was human interaction, trade, and less distinction between sidewalk and street.

When cars first filled the streets, cities experienced a fair bit of mayhem.3 It took decades before social norms, infrastructure, and regulation sorted out parking and driving.

In 1923, concerns with street safety led Cincinnatians to sign a petition to limit car speeds to 25mph within city limits. To quash this effort, the automobile lobby introduced the concept of jaywalking, passing laws restricting pedestrian access to the street across the country.4

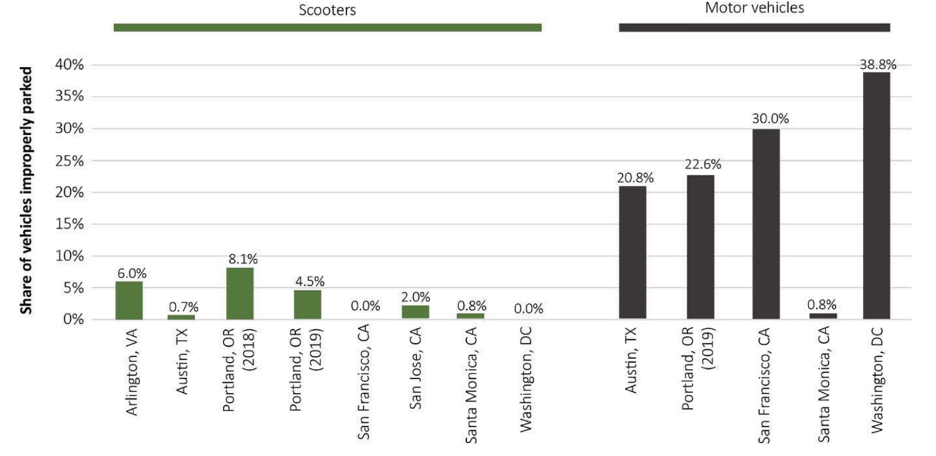

Thus, the street became the jurisdiction of the car and not the person. This concept is now so ingrained that most people today do not perceive cars as “clutter,” even when cars more frequently block access than scooters.5

As cities around the world test new street designs and norms, we are beginning to see what’s possible with micromobility. Amsterdam transformed its streets from congested, polluted avenues to human-focused places (see below). In the image at right, notice how many micromobility devices can park in the footprint of a single automobile.

Like the early days of the car, cities have to determine how to integrate shared scooters into busy streets. Unlike cars, scooters have the potential to reduce harmful emissions and improve space efficiency and safety. Planners should integrate micromobility into “complete streets,” prioritizing safety for all users and sustainability.

Micromobility parking should:

- Stay tidy and clear of pedestrian and vehicle paths.

- Enable ubiquitous access, with public transit integration to fill last-mile gaps.

- Support a low-friction experience for riders.

This last point is key. Complex restrictions, especially when implemented without supportive infrastructure, make it difficult to use scooters. Shared micromobility must be an attractive enough option to compete with cars and be a part of everyday mobility. Broad no-parking zones can add significant time and reduce access. Rules like a locking requirement cause a 20 to 30 percent drop in ridership.6 Reduced ridership means scooters sit unused – then they really are just clutter.

To achieve good micromobility parking, cities should consider the following methodology:

- Dockless/free floating where appropriate, as it is the most convenient, affordable, and accessible form of shared micromobility, maximizing mode shift out of cars.

- In higher density neighborhoods, allot designated parking with both virtual (in-app) and physical markers.

- In those neighborhoods, parking must be clear and pervasive (at least one per block but ideally one per corner), with locations informed by ridership data. Light infrastructure (stencils, signage) is sufficient, as well as affordable and flexible.7

The future doesn’t have to be the same as the past. Cars didn’t always dominate our streets. A global rethink of public space is already underway, with expanded outdoor dining and parklets replacing parked cars in hundreds of cities. Micromobility, when well planned for, can further help cities prioritize people over cars.

The bicycle, which, 10 years ago, was a curiosity, is now a necessity. It is found everywhere. Ten years from now, you will be able to buy a horseless vehicle for what you would pay today for a wagon and a pair of horses.

Thomas Edison, 1895

About the Author:

Andrea B. Korb is the Director of Legislative Policy for Bird Rides, Inc.

Sources:

- [1] Surveys by the City of Santa Monica found nearly half of scooter trips replaced car trips. Independently conducted surveys indicate 36% – 49% of scooter trips replace car trips (Intelligent Transportation Systems Joint Program Office, National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) 2019 State of the Industry Report, North American Bikeshare & Scootershare Association (NABSA) 2020 State of the Industry Report).

- [2] Kim, Kyeongbin and McCarthy, Daniel, Wheels to Meals: Measuring the Impact of Micromobility on Restaurant Demand (June 10, 2022). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3802082 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3802082

- [3] Bill Loomis, The Detroit News, “1900-1930: The Years of Driving Dangerously,” (April 26, 2015).

- [4] Greg Hand, Cincinnati Magazine, “How Automobiles Chased Cincinnati’s Pedestrians onto the Sidewalks,” (May 25, 2021).

- [5] Klein, N. J., Brown, A., & Thigpen, C. (2022, February 15). Clutter and compliance: Scooter parking interventions and perceptions. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/su8wx.

- [6] Based on Bird ridership data pre and post the introduction of the lock to requirement in several cities.

- [7]The Norwegian Institute of Transport Economics (TØI) analyzed the implementation of scooter parking infrastructure and found no difference in efficacy between heavy infrastructure, e.g. racks, and spaces that are indicated only with paint and geofencing. The study also found parkings compliance is higher when parking spaces are located in places that correspond to common ride end areas.