The severity of the COVID-19 pandemic and the unprecedented local government response resulted in historic federal funding to cities, towns and villages of all sizes through the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA). These funds supported municipalities in their response and recovery as well as provided a once-in-a-generation opportunity to direct flexible funding towards local public health. Through the State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF) program, ARPA enabled localities to address immediate health challenges caused by the pandemic, and to tackle longstanding health inequities that the pandemic further exacerbated. With less than a year left to obligate funds, ARPA funds can still have a positive impact on local public health.

The National League of Cities (NLC) recognizes the many factors that affect the stability of our lives. Housing, food access, employment, environmental hazards, and our level of social connectedness are all instrumental to individual and public health. Viewed this way, SLFRF investments in many spending categories have public health benefits. In this blog, we focus specifically on local SLFRF investments in the Public Health spending group, including those related to health services, COVID-19 response, remediating environmental threats to health, health inequities, substance use and mental health, and social isolation. This blog highlights these various spending ideas so localities can find ways to meet the 2024 obligations deadline; however, be sure to review Treasury’s Final Rule for compliance and reporting guidance.

As of September 2023, within the Public Health spending group, Tier 1 cities and consolidated cities have obligated:

- 76% of Public Health funds to COVID Response

Examples: COVID-19 testing and contract tracing, personal protective equipment, public vaccination campaigns, building new health centers - 17% of Public Health funds to Mental Health

Examples: Grief support services, behavioral health training and workforce development for healthcare, stabilization housing services, suicide prevention, crisis intervention programs, reducing social isolation, mental health services for city staff (for example, workforce support strategies for public safety workers as outlined in the ARPA 3-Year Public Safety Blog. - 4% of Public Health funds to Other Public Health

Examples: Building new health clinics, monitoring air quality, supporting emergency operations, youth dental care services, PFAs awareness, climate (heat) relief, youth gun violence prevention, optical services, lead remediation grants - 3% of Public Health funds to Substance Abuse and Addiction

Examples: Housing and support services, sobering centers, peer support services, workforce training and job placement services, community engagement activities

Although the above data represents the spending pattern of the largest cities in the US, municipalities of all sizes have made meaningful investments using ARPA to improve the health and wellbeing of their communities.

Spending Opportunities

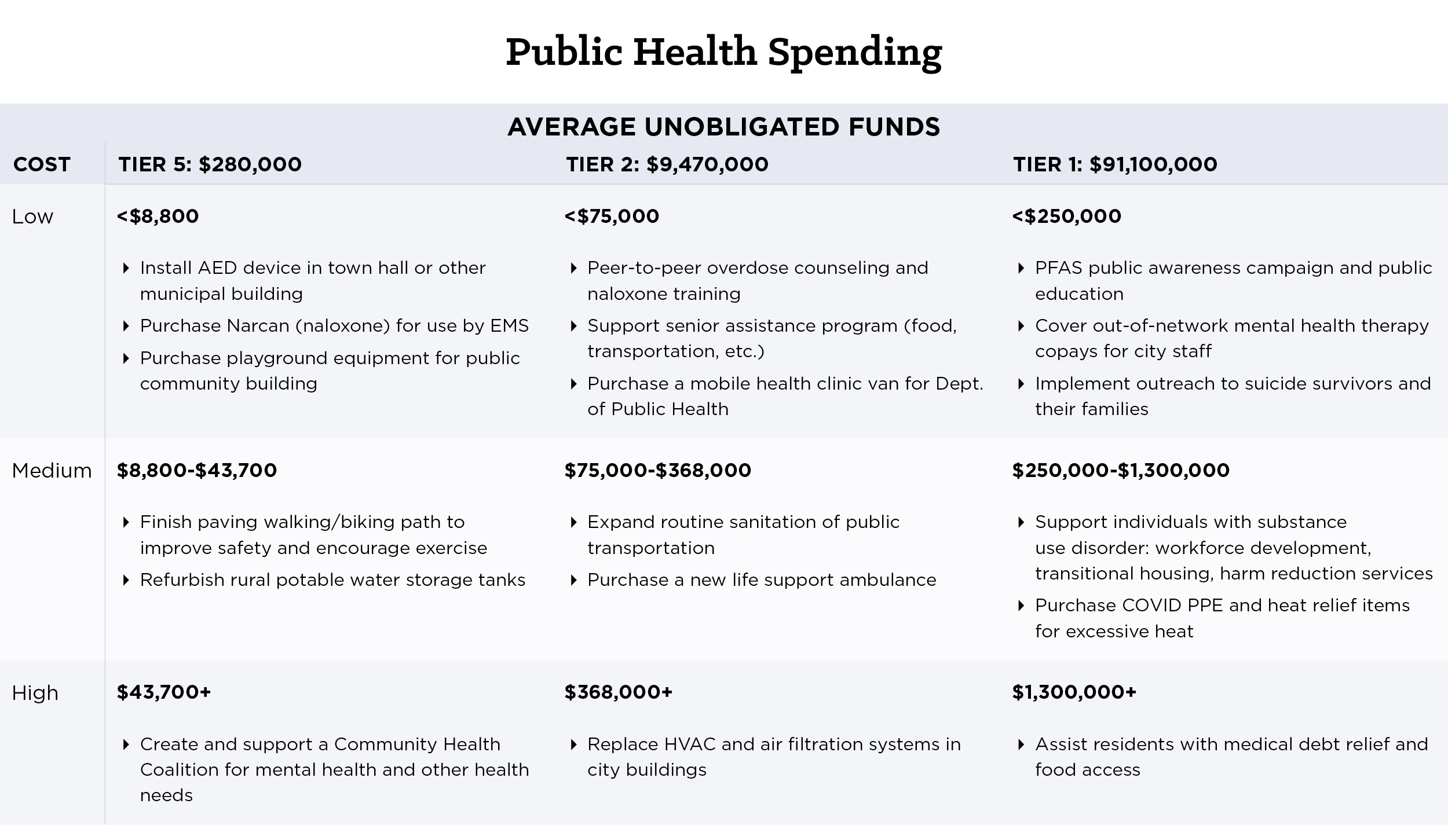

The spending opportunities in the table below include public health spending examples from municipalities of varying sizes with different categories of spending (low, medium, and high cost) to obligate remaining funds. The Public Health spending category was developed in partnership with NLC, Brookings Metro, and the National Association of Counties for the Local Government ARPA Investment Tracker. This resource is another tool for local leaders to find thousands of project ideas across tiers.

Local Spotlights

- Henderson, NV allocated nearly $31,000 to a wellness center that supports employee counseling, training and education on mental health-related emergencies.

- New Haven, CT allocated $749,000 towards several public health-related initiatives, including expanding hours at the city’s Homeless Health Hubs, purchasing a mobile shower for unsheltered individuals, securing harm reduction supplies to address opioid overdoses, and funding a full-time Homeless Health Outreach Coordinator.

- Pittsburgh, PA invested $4 million to support resident needs, including assistance with medical debt relief and food access.

Investing for Long-term Health

As local leaders direct their remaining SLFRF investments towards supporting current and long-term health needs in our nation’s cities, towns and villages, it is also important to consider how to maximize the impact of these investments by:

- Funding meaningful community engagement and centering lived experience. Aligning these once-in-a-lifetime investments with community needs and desires can go a long way toward building trust in local government. In many cases, ARPA funds can be used to fund community engagement and planning processes for programs or projects with public health goals.

- Investing in data infrastructure and evaluation. Collecting data and integrating data systems can help the efficacy and sustainability of city programs. These investments help ensure that future public health decisions are data-informed, which will help make the case for future (especially federal) funding.

While the time to obligate ARPA funds is running short, many federal agencies also have funding opportunities that may overlap with local public health goals that can support the long-term needs of your community.

- Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) – Health workforce, rural health, maternal health, etc.

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) -Climate change, hazard remediation, environmental quality, environmental justice, PF children’s health, PFAS, etc.

- Housing and Urban Development (HUD) – Homelessness, supportive housing, healthy housing, etc.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) – Broad public health: disease prevention, violence prevention, wastewater monitoring, etc.

- Health and Human Services (HHS) – Broad public health: behavioral health and substance use, etc.

- National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) – Social cohesion and connection, arts & health, etc.

- Department of Transportation (DoT) – Rural transportation, safe streets, etc.

Glossary

American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) is the $1.9 trillion economic stimulus and pandemic recovery legislation signed into law by President Joe Biden on March 11, 2021. This blog and its series focus on the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF) program; therefore, authors may use “ARPA” and “SLFRF” interchangeably.

Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF) is the $350 billion program authorized by ARPA that provides economic stimulus and pandemic recovery funding to U.S. states, territories, cities, counties, and tribal governments.

Allocations are the total funds distributed to state and local governments through SLFRF.

Adopted Budget are dollars distributed to local governments through SLFRF that have been budgeted or committed to specific initiatives or programs.

Spent means the grantee has issued checks, disbursed cash, or made electronic transfers to liquidate (or settle) an obligation.

Obligations are dollars distributed to state and local governments through SLFRF that have been legally dedicated to specific uses, frequently (but not exclusively) through contractual agreements. The Treasury’s recent guidance defines obligations as “orders placed for property and services and entry into contracts, subawards, and similar transactions that require payment.” The Final Rule requires recipient local governments to obligate 100 percent of their SLFRF allocations by December 2024.

Tier 1 local governments are metropolitan cities and counties with populations greater than 250,000. These jurisdictions include states, U.S. territories, and counties but NLC’s focus for this series is on cities. These governments are required to report quarterly, and the last reporting date captured in our data is from September 30, 2023.

Tier 2 local governments are metropolitan cities with a population below 250,000 residents that are allocated more than $10 million in SLFRF funding, and NEUs that are allocated more than $10 million in SLFRF funding. These jurisdictions include counties but NLC’s focus for this series is on cities. These governments are required to report quarterly, and the last reporting date captured in our data is from September 30, 2023.

Tier 5 local governments are metropolitan cities with a population below 250,000 residents that are allocated less than $10 million in SLFRF funding, and NEUs that are allocated less than $10 million in SLFRF funding. These jurisdictions include counties but NLC’s focus for this series is on cities. These governments are required to report yearly, and the last reporting date captured in our data is from April 31, 2023.

Non-entitlement units (NEUs) are local governments that typically serve 50,000 residents or less. Of the $65.1 billion allocated to municipal governments across the country, SLFRF allocated $19.5 billion, or 30 percent, to NEUs. Comparatively, SLFRF allocated $45.6 billion, or 70 percent, to metropolitan cities. Depending on if an NEU is a Tier 2 or Tier 5 recipient, they may have different reporting requirements.

Acknowledgements: Thank you to Christy Baker-Smith, Julia Bauer, Irma Esparza Diggs, Josh Franzel, Patrick Rochford, Archana Sridhar, and Melissa Williams for their support and review of this blog.