For the first eight months of the groundbreaking State and Local Fiscal Recovery Fund grant program, enacted under the American Rescue Plan Act, local government grantees operated under an “interim final rule”. The interim rule was sufficiently clear on eligible expenditures to address immediate emergency needs related to losses stemming from COVID-19, and many cities and towns made their first grant expenditures to address those immediate needs. The interim rule also provided additional flexibilities for local governments to intervene in declines impacting individual households and small businesses in their communities; and to make community-wide improvements in water, sewer, and broadband. However, to meet the urgent need to deliver grants to state and local governments quickly, the interim rule was published without clear direction for every category of spending, and many questions from local leaders were not answered. As a result, some cities and towns pressed pause on grant expenditures until a final rule was released.

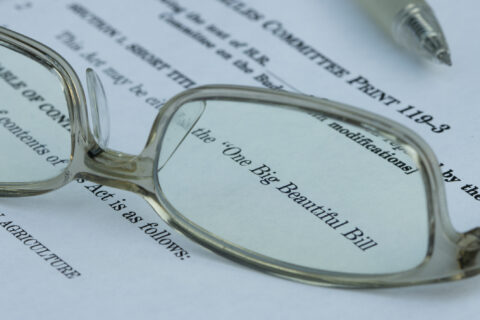

Last week, on Thursday, January 6th, the U.S. Department of Treasury (Treasury) released their Final Rule for the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF). The new Final Rule is more comprehensive and significantly longer than the interim rule, arriving at over 400 pages. Most of the new content is aimed at providing greater clarity, direction, and examples for rules that were already in effect under the interim rule. There are also a few important changes that local leaders should know. Promisingly, most of the questions and recommendations raised by NLC in its comment letter to Treasury on the rule have been answered or acted on.

For cities and towns that have delayed obligations and expenditures of their initial ARPA SLFRF grant, and before any local government obligates the second half of their grant, here are ten things to know about the final rule:

1. The final rule provides more direction and greater certainty for local governments.

The Coronavirus Local Fiscal Recovery Fund (CLFRF) remains an urgent lifeline for local governments, and their residents, that experienced losses or other declines related to the COVID-19 pandemic. In recognition of the fact that thousands of local governments continue to operate at some level of reduced capacity, the final rule has significantly expanded to cover both activities that grantees can do, and provides significant new direction and examples of how to do it. In that sense, the final rule goes beyond typical “government speak” to be more useful for both experienced practitioners and those who are new to federal grant management.

Many expenditures that were implied by interim rule are fully spelled out in the final rule, including expenditures oriented to long-term recovery efforts such as rehabilitation and construction of affordable housing, facilities and services for childcare and early learning, violence intervention and deterrence activities, job training and workforce supports, and financial services for unbanked residents. To navigate the significantly expanded rule, Treasury has published a separate, short overview document for quick reference.

The final rule also points to new Treasury resources to make it easier for local governments to determine if specific neighborhoods or households meet the conditions for expenditures addressing low-income and disproportionately impacted residents. While the interim rule reduced regulatory and compliance burdens for expenditures made within Qualified Census Tracts, Treasury is also releasing a new Tool for Determining Low and Moderate Income Households in conjunction with the release of the final rule.

2. The final rule does not penalize local governments for rule changes that impact already spent funds.

The final rule takes effect on April 1, 2022 and until that time, the interim final rule remains in effect. However, grantees have been permitted flexibilities and protections during the transition. For one, local governments do not need to wait until April to take advantage of rules changes and expanded eligibilities. They can start spending in accordance with the final rule immediately. Secondly, local governments will not be penalized with enforcement actions for expenditures made before April 1, 2022 that are consistent with the interim final rule, but that may be subject to greater limitation or restriction by the final rule. In a statement, Treasury provides a list of reasonably anticipated differences between the interim and final rules that may impact grantees’ plans. But the transition flexibilities and protections end when the final rule takes effect. Bottom line, all state and local governments must be in compliance with the final rule beginning on April 1, 2022.

3. The final rule makes it easier for small cities and towns (NEUs) to spend in familiar ways.

The most flexible spending category under the SLFRF grant program is “Replacement of Lost Revenue” for government services, which the final rule says generally includes any service traditionally provided by local governments. To take advantage of this category of spending, the interim rule required all grantees, regardless of size, to perform a complex calculation to determine how much revenue a locality could claim as lost.

The final rule presents a significantly simpler option by permitting local governments to choose a “standard allowance” for lost revenue of $10 million for the lifetime of their grant. Local governments may continue to use the amount provided under the calculation, but for those that select the standard allowance, they may use up to $10 million for government services with streamlined reporting requirements compared to those that choose to stay with their calculated amount.

In practice, almost no Non-Entitlement Unit of local governments received a grant larger than $10 million under the SLFRF program. So in effect, the rule excuses almost local governments with fewer than 50,000 residents who received their grant through their state from requirements associated with the calculation of lost revenue, if they choose, and instead allows all those smaller cities and towns to claim the standard allowance.

4. The final rule more accurately reflects municipal budgeting by expanding sources of revenue.

The final rule removes a limitation imposed by the interim rule on the type of local revenue sources that could be included in calculations of lost revenue. The interim rule specifically excluded municipally-owned utility revenue from calculations of general revenue. In the final rule, Treasury adjusts the definition of general revenue to allow governments to choose whether to include revenue from their utilities in their revenue loss calculation. The final rule also clarifies that municipal revenue derived from liquor store revenue is part of general revenue. Although the new standard allowance has made these changes less consequential under the SLFRF program, the more accurate definition of general revenue embraced in the final rule is welcome, and has the potential to positively impact federal legislation and regulation impacting cities in the future.

5. The final rule eases limits on hiring and retention activities, and other capacity building measures.

The interim final rule permitted local governments to use grant funds to address furloughs and lay-offs by allowing expenditures to bring municipal employment up to pre-pandemic levels, but not to support hiring above the number of those employed by a municipality on January 27, 2020. The final rule adds local government capacity to their consideration of expenditures for municipal employment. Among the changes, recipients may use SLFRF funds to rehire staff for pre-pandemic positions that were unfilled or eliminated due to the pandemic without undergoing further analysis. Alternatively, local governments may pay for payroll and covered benefits to increase its number of budgeted full-time equivalent employees up to 7.5 percent above its pre-pandemic employment baseline, which would help local governments make up for underinvestment in the public workforce since the great recession.

In terms of retention in the face of economic hardship that many local government employees faced during the pandemic, the final rule allows local governments to use grant funds to provide additional funds to workers who experienced pay cuts or were furloughed. According to the final rule, a local government “must be able to substantiate that the pay cut or furlough was substantially due to the public health emergency or its negative economic impacts (e.g., fiscal pressures on state and local budgets) and should document their assessment. As a reminder, this additional funding must be reasonably proportional to the negative economic impact of the pay cut or furlough on the employee.”

6. The final rule clarifies which employees are eligible for premium pay in both the public and private sector; and makes it clear that elected officials are not eligible for premium pay.

Under the interim rule, there was ambiguity about whether employees of public works; public utilities; courthouse employees; police, fire, and emergency medical services; and waste and wastewater services employees were eligible for premium pay as public sector employees. The final rule clarifies “all public employees of local governments are already included in the definition of ‘eligible worker.’”

Non-public employees can also be eligible for premium pay, and the final rule simplifies requirements on local governments governing these expenditures. The chief executive of a local government may designate these workers “as critical, in order to receive premium pay.” However, non-public workers still must meet the other requirements for premium pay. For example, performing essential work. Treasury will defer to the chief executive’s discretion in making the designation, and a local government does not need to submit for approval its designation to Treasury.

Although local governments can award premium pay to non-hourly or salaried employees, as well as part-time employees, the final rule clarifies that elected officials are not eligible for compensation under the premium pay category. Volunteers are also excluded from eligibility for premium pay.

7. The final rule recognizes a broader set of eligible activities that respond to public health, economic harm, and disproportionate impact.

The final rule improves on the interim rule by providing expanded lists of enumerated eligible uses that are responsive to questions submitted by local government grantees. The expanded lists of eligible activities fall under the following categories:

- public health,

- assistance to households,

- assistance to small businesses,

- assistance to nonprofits,

- aid to impacted industries, and

- public sector capacity.

The final rule also clarifies and expands the types of populations that may be presumed to be “impacted” and “disproportionately impacted” by the pandemic without additional documentation. “Impacted” and “disproportionately impacted” are defined categories that unlock grant spending for broader ranges of activities. Among the simplifications resulting from this change, local governments may presume any small business or nonprofit operating inside a Qualified Census Tract is eligible for aid as a disproportionately impacted entity.

8. The final rule clarifies whether certain capital expenditures are allowable or not.

The final rule clarifies that local governments can use grant funds for capital expenditures that support an eligible COVID-19 public health or economic response. For example, local governments may build certain affordable housing, childcare facilities, schools, hospitals, and other projects consistent with final rule requirements. The final rule also prohibits certain capital expenditures, including those for construction of new correctional facilities (jails) in response to rising crime; construction of new congregate facilities as a way to decrease the spread of COVID-19 within such facilities (such as large congregate homeless shelters); or construction of convention centers and stadiums.

9. The final rule expands eligible water, sewer, and broadband projects

The final rule broadens eligible broadband infrastructure investments to address challenges with broadband access, affordability, and reliability, and adds additional eligible water and sewer infrastructure investments, including a broader range of lead remediation and stormwater management projects. Like other expenditure categories, the final rule expands the list of specific enumerated uses for water, sewer, and broadband to simplify determinations of eligibility.

10. The final rule maintains restrictions on spending that is not prospective.

The final rule is consistent with the interim rule on overarching spending restrictions irrespective of category. In general, restrictions reflect the principle that grant funds must be used prospectively, rather than retrospectively. Among the specific restrictions, local governments may not use grant funds to address pension fund liabilities; to replenish financial reserves; for payments on bonds or other debt services; or payments required by settlement, judgment, or consent decree.

Let NLC deliver for you!

The National League of Cities (NLC) is your partner in recovery. This is the time for America to do more than survive; we can thrive.

NLC is a strategic partner for local leaders and municipal staff, serving as a resource and advocate for communities large and small. Click the button to learn how NLC can help deliver for your city.