“Streets and their sidewalks—the main public places of a city—are its most vital organ.” Jane Jacobs knew something that was somehow forgotten for decades by American planners: streets—specifically sidewalks—are the main theater for American democracy, and the health of our streets is inextricably related to the health of our democracy. Cincinnati’s history is all too familiar for urbanists: a growing metropolis stunted by suburbanization, industrial consolidation and racism. Fortunately, in the past few years, Cincinnati’s population is growing and many of our neighborhood business districts are thriving. Unfortunately, we cannot escape all of the ailments associated with the design decisions made during the 20th century: our transportation system is by and large designed for cars.

Like many other cities, designing our city for cars has been a tragedy resulting in 36 deaths this year alone due to traffic violence. Walking, riding, rolling, and even driving can be a terrifying experience because of the choices made by previous iterations of elected officials and planners to build mini highways through our neighborhoods. These choices have also had detrimental effects on our democracy. First, when streets are designed for cars, people take notice and no longer congregate on sidewalks. It becomes unsafe, uninviting, and it is much more comfortable to stay inside. Second, by designing a car-dependent society, we eliminate the freedom of choice for peoples’ transportation decisions, which has led to a more inequitable, less healthy and more isolated society. The result is that residents are forced to either buy a car, which on average costs about $10,000/year, or try to get around via public transit, which in many cases means not having access to a grocery store or a job.

It took decades to get us into this situation, and it is going to take decades—and dollars—to reverse it. Luckily, Cincinnati is making strides towards making those improvements. In 2020, voters in Cincinnati passed a historic sales tax levy that is improving our bus system—bringing more reliable service today and creating Bus Rapid Transit over the next several years. Additionally, I spear-headed the recently approved Complete Streets ordinance. For me, the health of our democracy is at the heart of Complete Streets. Complete Streets are streets where people want to hang out—not just places of rapid movement and transient interactions. It means making our sidewalks “third spaces” where public discourse can thrive, and a sense of community and therefore democracy can flourish. We want our streets to be designed for the safety and comfort for vulnerable road users. We want walking, cycling, rolling and taking the bus to be irresistible forms of transit for Cincinnatians of all ages and abilities. This is the philosophical underpinning of our Complete Streets ordinance.

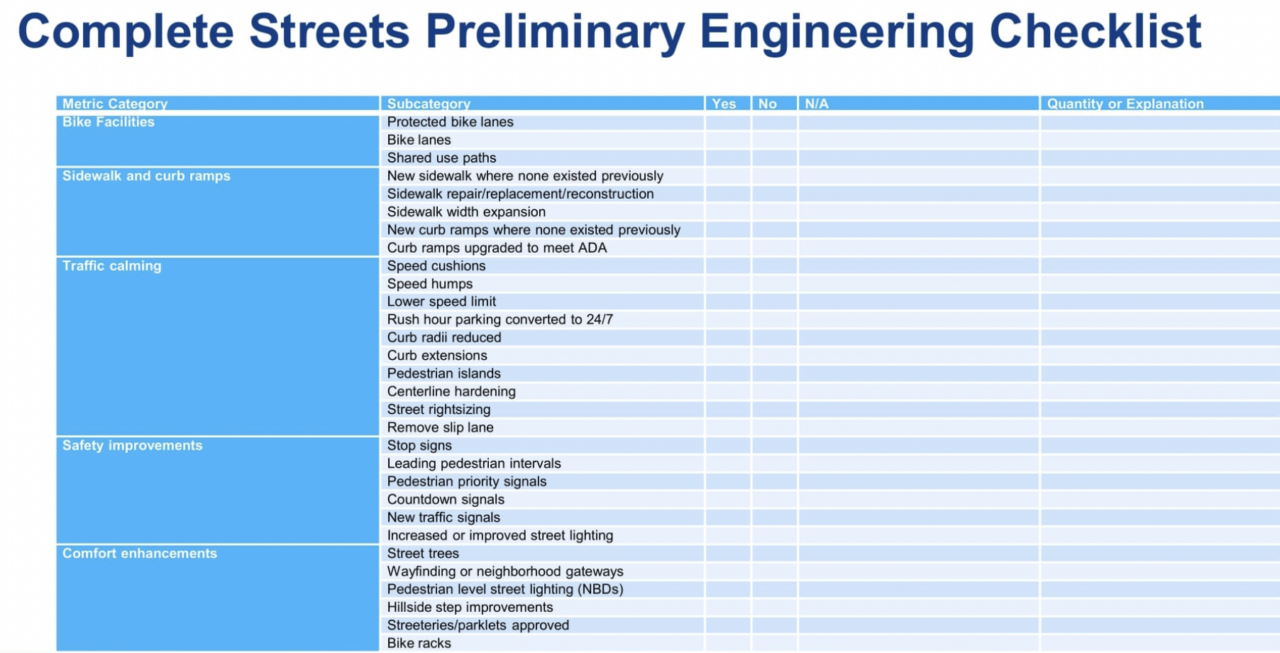

Now, every time the City repaves a street, it will look at a Complete Streets scoring rubric and evaluate which improvements can be made. When Complete Streets improvements are not made, the City will have to justify why we didn’t make those enhancements. This public reporting mechanism brings a huge amount of transparency to the City’s engineering process. It’s not only what we do, its how we do it, and our Complete Streets ordinance systematically unwinds the auto-first design decisions made over the past century in a public, transparent manor in favor of people-first design decisions. By improving public transit and redesigning our streets for people, we are enhancing the built environment in which public life can thrive while giving travelers the freedom and choice to take public transit, walk, bike or drive. Freedom and choice are of course core tenets of a healthy, functioning democracy.

With the recently passed Federal Bipartisan Infrastructure bill and other federal investments, there are even more federal dollars to enable Cincinnati and other communities to help bend the curve toward streets built for people. One great example of this is a $20 million RAISE grant that Cincinnati received in September to reconnect a part of the West End neighborhood in Cincinnati that saw 25,000 people displaced with the building of I-75. This is just the beginning of how Cincinnati will leverage federal dollars to unwind choices made to build infrastructure through communities rather than to communities. It’s a stride forward to improve our public realm.

But designing for democracy is not only relegated to the built environment of our streets. As a community, Cincinnati is taking a critical look at our zoning code to explore how we can promote a private built environment that promotes active and public transportation, as well as our democracy. Each of these changes cannot be taken in isolation—they are about creating a system for equitable growth and a city built for people. We can build a city where democracy thrives. For me, that means a Cincinnati that has a thriving public life and provides equitable housing and transit choices for all residents is that city. Our historic investment in public transit and perspective shifting Complete Streets Ordinance is the bedrock of that progress, and we are just getting started.

About the Author

Mark Jeffreys is a member of the Cincinnati City Council in Ohio.