In April 2022, NLC and the National Assembly of State Arts Agencies (NASAA) convened local leaders in health and the arts to discuss how artists, in collaboration with government, can meaningfully impact health outcomes in communities. What follows are excerpts from a facilitated conversation between Anisa Raoof (Rhode Island State Council on the Arts), Steven Boudreau (Rhode Island Department of Health), Gina Rodríguez-Drix (Providence Department of Art, Culture + Tourism), Jazzmen Lee-Johnson (2019 Rhode Island State Health and Human Service’s Artist in Residence) and Melody Gamba (2022 Rhode Island State Health and Human Service’s Artist in Residence).

The conversation features two Rhode Island programs. The Health and Human Service’s Artist in Residence is a collaboration between Rhode Island State Council on the Arts (RISCA) and Rhode Island Department of Health (RIDOH) to embed the arts within the healthcare system and achieve the goals outlined in the Rhode Island State Arts and Health Plan. The City of Providence’s Creative Community Health Worker program is a collaboration between Providence’s Department of Art, Culture + Tourism and Healthy Communities Office to train artists to be certified Community Health Workers.

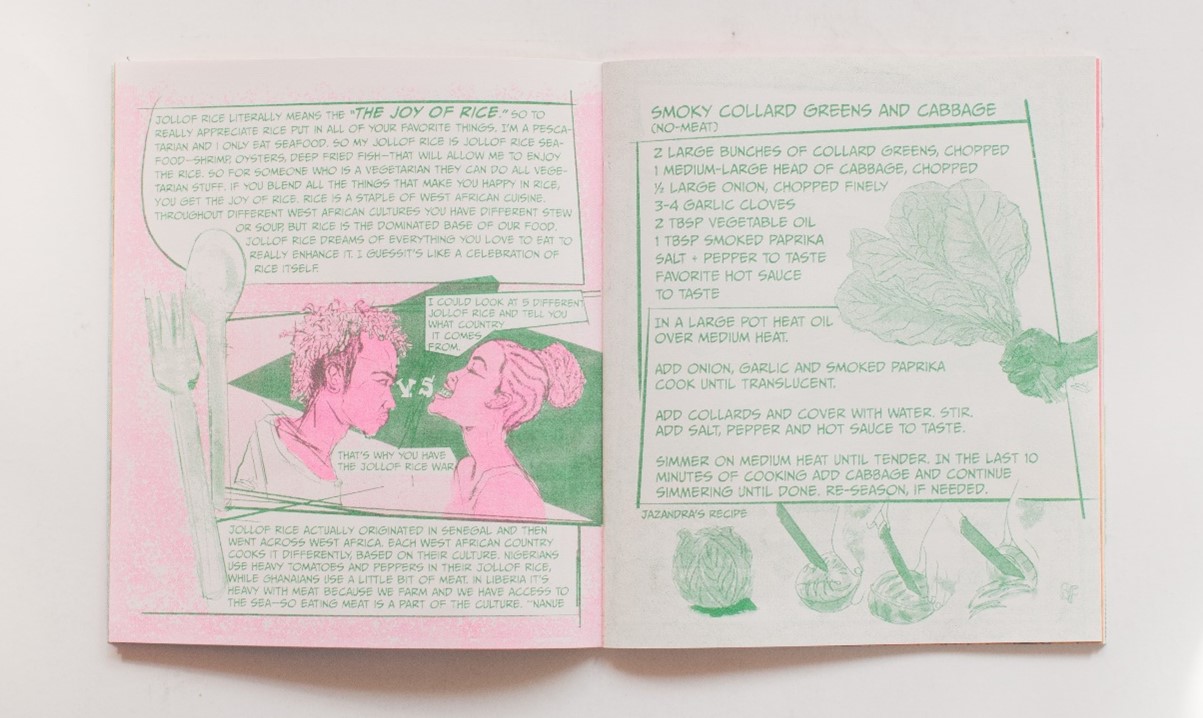

During the inaugural Rhode Island State Health and Human Service’s residency, Jazzmen Lee-Johnson drew upon her skills as a visual artist, scholar, composer and curator to engage with the historical causes of health disparities in Rhode Island. She helped support the communication of public health information as well as community-based group trauma sessions. She also produced a graphic novel cookbook focusing on nutrition for refugee communities. Melody Gamba was recently selected for the 2022 residency to connect community, health resources and the arts.

The five Providence-based artists participating in the Creative Community Health Worker program undertook 70 hours of training to become Rhode Island certified Community Health Workers, equipping them to address the social determinants of health through artistic partnerships with community-based organizations.

This is part three in a blog series produced by the National League of Cities and the National Assembly of State Arts Agencies. The arts and creativity are increasingly recognized as necessary infrastructure for healthy, prosperous and equitable communities regardless of community size or geography. This blog series highlights policies and programs that leverage the power of the arts to engage communities and improve well-being. These conversations and stories provide inspiration and examples for local leaders looking to engage their jurisdictions through the arts and creativity with the help of state and federal resources.

Q: Why should local leaders involve artists in the healthcare work of their communities?

Steven Boudreau: There is a growing lack of confidence in the work that we do in public health. This was exacerbated by the political climate during the pandemic: I think people were given permission to question in ways that they never have before; We are calling it a crisis of confidence now more than ever, because that’s what we’re recognizing it as—more of a heightened sensitivity around this distrust and the things we can do to combat that or recognize it and act. It’s true that medicine and public health are fraught with uncertainty and ambiguity, but artists use that as the starting point in the conversation. Artists can help governments and elected leaders lean into and move through this distrust with communities and their leaders.

Gina Rodríguez-Drix: In Providence, we had this organic growth around the intersection of place, arts and health. Two things came out of that: one is more clarity around the connection between arts and health; and the other was that artists are really incredible facilitators. So, we embedded artists in our process as facilitators, not only for their disciplinary expertise but for their ability to facilitate community and relationship building.

As artists and arts administrators, could you discuss your role in addressing this “crisis of confidence”?

Jazzmen Lee-Johnson: Every project during my residency was an opportunity for me to assist in community building. In joining the ongoing work of the Rhode Island Department of Health, I connected with staff through group artistic practices. With the graphic novel cookbook we created, I helped foster a relationship between RIDOH and refugee communities. With the Office of Asthma, we were able to look at the data and create a public art project that communicates the connection between historical industrialization, racism and the current impact of pollution on health for people living in the Port of Providence. Through it all, I met with people in different state departments and got them excited and discussed possible artistic collaborations, and that’s just not an experience that many people, in the arts or public health, get to have, and I think it has really moved me and my creative practice.

Melody Gamba: The public health artist in residence centers the arts and invites us to think differently on how to approach systemic and policy change on a state level. Being an artist, I am not always looked at as a scholar or an important voice in the room towards change making, so to see government agencies make this work a priority was validating and encouraging. Building upon the community-engaged artmaking already happening in RI, I plan to use shared art making as a tool to engage in community conversations and hope to shift towards rupture and repair, connection, and increased trust.

Anisa Raoof: Forging this partnership between a state arts and health agency validates and elevates the importance of arts-based approaches to address public health priorities. Making space for artists to share their creative practice in the application and interview process was informative and even prompted the Arts Health team to reimagine what this program could be. Shifting focus from project-specific to be more process-oriented changes the way we work within state agencies and our impact in the community. It’s a new way of thinking about how to come together and create something lasting.

Q: Melody and Jazzmen, How do you position yourself between working for a government agency and working with historically marginalized communities, which—for good reasons—often have lower levels of trust in government?

Melody Gamba: I acknowledge that I am not the expert in the room. I have skills to share, but I’m really learning from and following the lead of the community. Questions I consider are: Who are the community voices? What are the community needs? What is missing? I acknowledge that the community has the personal tools and the knowledge, and I hope in my role that I can build relationships and trust to serve as a bridge to the community and government agencies and work towards dismantling systemic oppression.

Art gives us the power to be creative and imagine what health equity and our systems could look like without systemic racism. Without creativity and imagination, how can we begin to think about community liberation and how we can make change?

Jazzmen Lee-Johnson: Through my residency I saw that there were lots of gaps that I could not fill. There’s a lot of disconnect between communities, especially oppressed communities, and government entities. I feel privileged that I was able to straddle both worlds; that I could go back to a government office and relay community concerns. But there are also times when you’re representing the Department of Health and communities would rather not work with you. So, I think it’s really complicated. People have been through a lot and there have been many moments in history when communities say, “No, I do not trust the structures of power or access, especially around health, especially in communities of color.”

I think that the potential here is, and this is a big ask, for an artist to exist in both worlds. They can build respect and trust amongst the community and also have access to, for example, the Department of Health and see the ways in which they can work together.

Q: How can you make your project, which officially lasts only six months, sustainable for both artists and as a long-term program beyond your tenure?

Melody Gamba: First, I acknowledge there is no quick fix, and this is a first step of many. One goal of this project will be cultivating sustainability beyond the 6-month residency.

I believe when we start using art as a part of our daily practices, it gets us more comfortable with not being in control, not having all the answers, and trusting our capacity to approach each challenge when it arises. With shared art-making, we have the potential to build a more cohesive collective and welcome more voices to the table, which supports collective solutions towards equitable and effective action.

Jazzmen Lee-Johnson: The question I worked with was, what would it mean to do this at the seed level, at the sprout level, at the plant level, and at the forest level? And even so, it was difficult to just plant the seeds. But it created a framework to move towards self-sustained projects. For example, because of our relationship with the Southside Community Land Trust, they came back this year saying they had applied for more grants, fundraised, created youth stipends and continued the work.

Gina Rodríguez-Drix: I think that, ultimately, if you are in public service the arts are about creating spaces of belonging. All we can really do is liberate resources. There’s a real importance for the public sector to be this pipeline, to create more opportunities for both artists and health workers to work together.

About the Authors:

- Steven Boudreau is the Chief Administrative Officer for the Rhode Island Department of Health and Co-chair of Rhode Island Arts and Health.

- Melody Gamba (she/her) is a dance artist, educator, licensed mental health counselor and board-certified dance/movement psychotherapist who is an advocate for inclusive, equitable and just educational outreach, therapeutic interventions, and social justice programming within her community.

- Jazzmen Lee-Johnson (she/her/hers) is a visual artist, scholar, composer, and curator whose practice centers on the interplay of animation, printmaking, music, and dance, informed by a yearning to understand how our current circumstance is tethered to the trauma of the past.

- Gina Rodríguez-Drix is the Deputy Director for the Department of Art, Culture + Tourism, City of Providence, RI.

- Anisa Raoof (she/her) is the Grants Management Fellow and the Arts and Health Coordinator at the Rhode Island State Council on the Arts. She is also co-chair of the Rhode Island Arts Health Initiative working in partnership with RIDOH to advance the integration of the arts, art-therapies, and health and well-being in Rhode Island.