The COVID-19 pandemic revealed vulnerabilities in America’s supply chain. Travel and trade restrictions as well as economic shutdowns through the pandemic have created global shortages for everything from computer chips to lumber. Shortages of production goods like these have disrupted the production of other goods like cars and computers. As a result, consumers face shipping delays and higher prices—inflation in 2021 was 6.8 percent, a forty-year high. These supply chain disruptions also have the potential to upend President Biden’s infrastructure plans. Due to the shortage of raw materials, commercial infrastructure is suffering and construction projects are being delayed or halted.

During his first State of the Union address, President Biden spoke candidly about the supply chain and inflation when he said, “The pandemic disrupted global supply chains. When factories close, it takes longer to make goods and get them from the warehouse to the store, and prices go up. Look at cars. Last year, there weren’t enough semiconductors to make all the cars that people wanted to buy. And guess what, prices of automobiles went up.”

To address supply chain disruptions and inflation, President Biden suggested that “instead of relying on foreign supply chains, let’s make it in America.” In other words, let’s reshore. But what is reshoring, and why might reshoring help alleviate some of America’s supply chain and inflationary stress?

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology Center for Transportation and Logistics describes reshoring as “a manufacturing location decision that is a change in policy from a previous decision to locate manufacturing offshore from the firm’s home location.” Reshoring can contribute to the expansion of America’s production and innovation capacity, a key strategy highlighted in the White House’s 2021 report, Building Resilient Supply Chains, Revitalizing American Manufacturing, and Fostering Broad-Based Growth. By improving our nation’s supply chain resiliency, our economy will be able to recover more quickly in the event of future major economic disruptions, such as another pandemic, war and climate disasters.

The Biden administration’s supply chain strategy identifies four industry sectors as critical supply chain sectors that are vulnerable and/or vital to America’s economic and national security. Those four sectors are:

- Semiconductor manufacturing and advanced packaging

- Large capacity batteries

- Critical minerals and minerals

- Pharmaceuticals and active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs)

Some major U.S. corporations within these critical sectors are already working with states, counties and cities to reinforce America’s supply chain. For example, Intel is investing $20 billion to build a semiconductor plant in New Albany, OH by 2025, a project that is expected to generate 3,000 jobs within the company. Intel’s $20 billion investment in New Albany is significant and will surely be a driver of economic and employment growth in the region, but how ready and willing is the workforce to take on these semiconductor manufacturing jobs and other jobs in critical supply chain sectors?

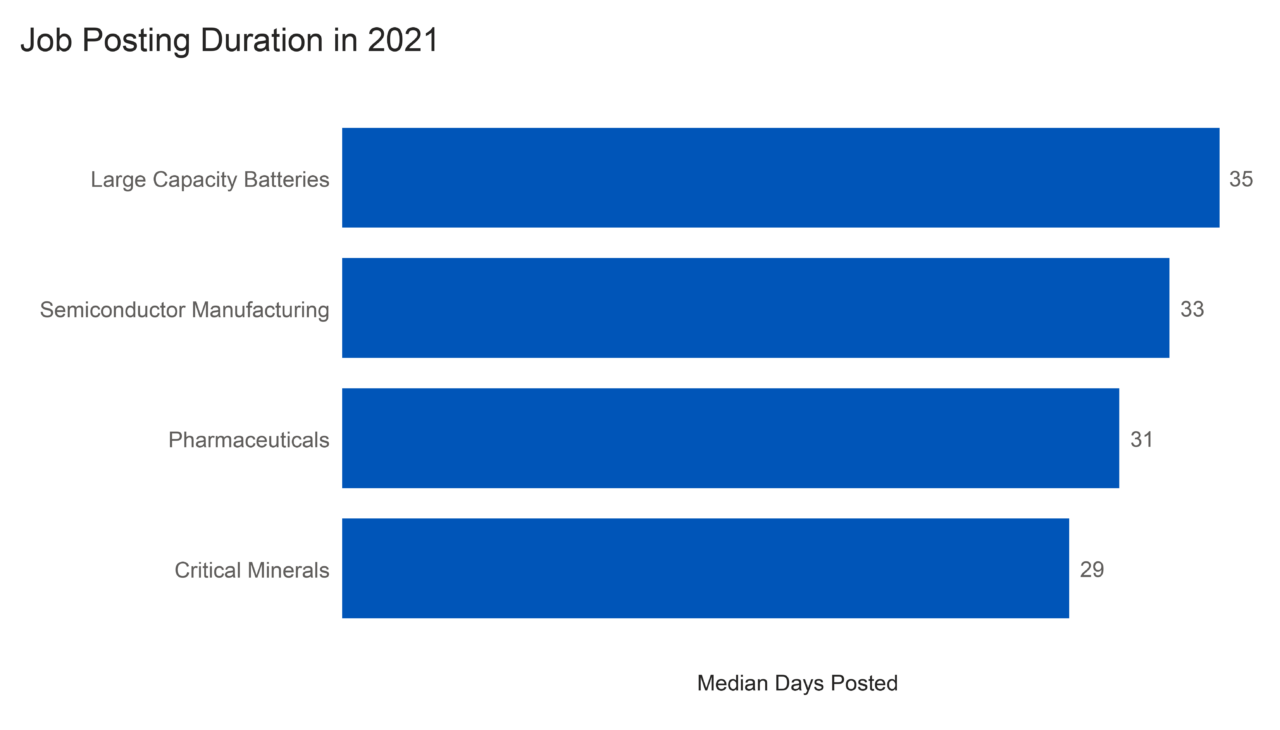

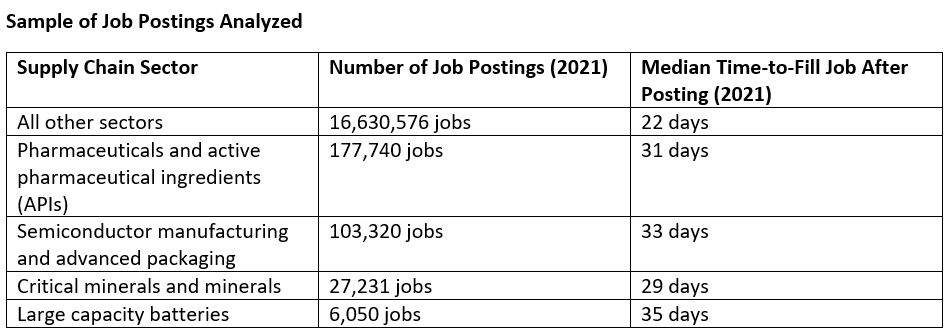

Across the country, the National League of Cities (NLC) found that jobs in all four of these critical supply sectors take at least seven days or 32 percent more time to fill than all other jobs, indicating a shortage of human capital.

NLC’s analysis of over 16 million job postings opened and filled in 2021 reveals that jobs in all four critical supply chains are significantly harder to fill than jobs in other sectors. We source unique job postings data from LinkUp, a company that scrapes data from thousands of company websites daily. By tracking when a particular job opens and closes, we can estimate the time it took to fill that job and compare it to millions of other jobs by occupation, industry, and location.

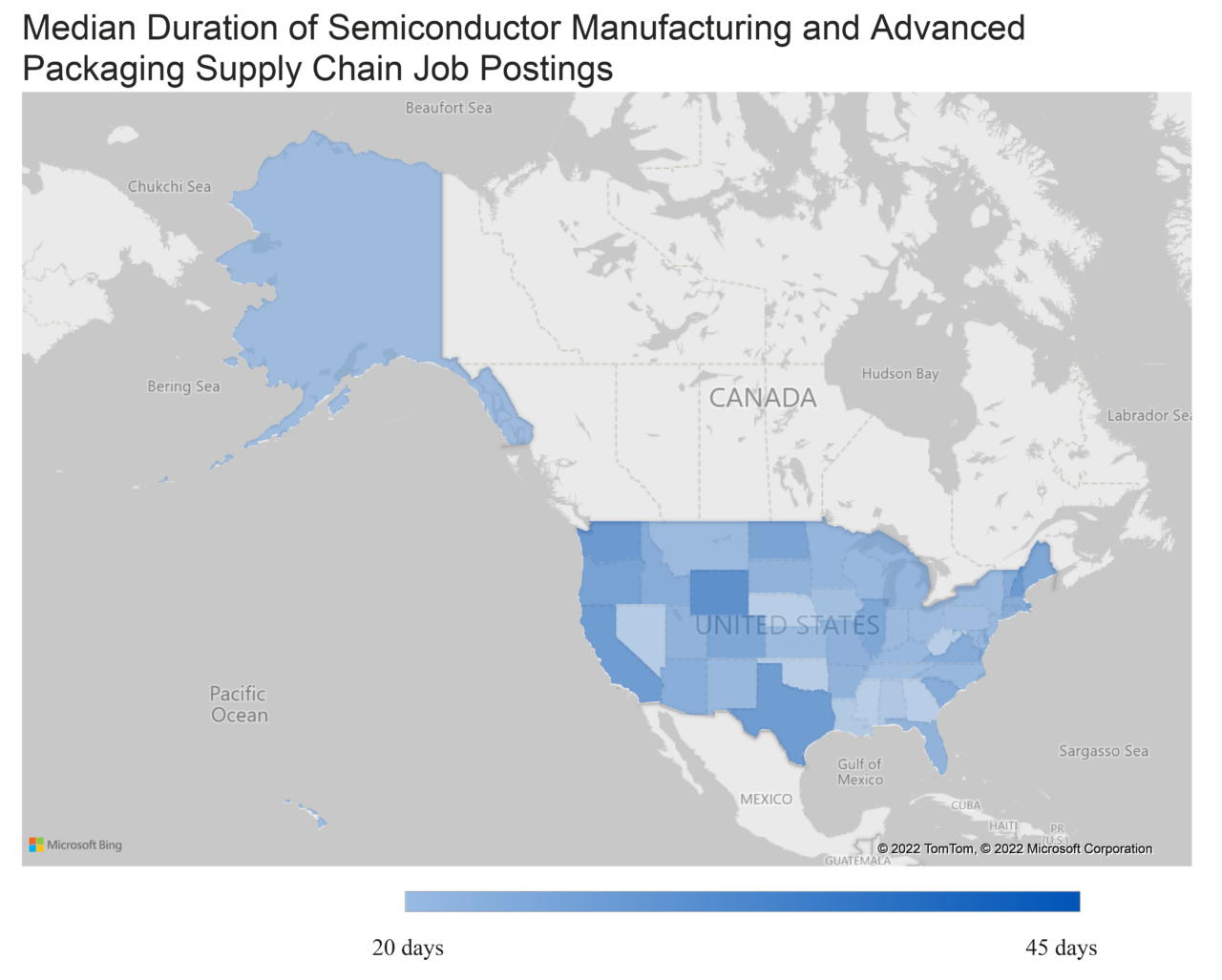

This data includes over 300,000 job postings that were opened and filled in 2021 related to one of the critical supply chains. Jobs were determined to be related to a critical supply chain if the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) classification of the company is related to one of the supply chains as outlined in the Biden administration’s plan to improve supply chain resilience. Our analysis indicates that the U.S. workforce is not prepared to meet this demand in any of those supply chains. Jobs in all four supply chains take longer to fill than other jobs. The most difficult jobs to fill are those in the semiconductor manufacturing supply chain, and jobs in large capacity batteries are a close second. Jobs in the semiconductor manufacturing supply chain take 33 days to fill (50 percent longer than all other jobs). Jobs in large capacity batteries take 35 days to fill on average (59 percent longer than all other jobs).

While less than two percent of jobs in this sample are tied to a critical supply chain, the demand for these sectors in the U.S. is expected in increase substantially as the White House invests in reshoring. One region expected to see jobs growing immediately is the Greater Columbus Ohio area, with Intel opening a semiconductor manufacturing operation that’s expected to add 3,000 jobs this year. According to our analysis, less than one percent of all jobs posted in Ohio in 2021 were related to semiconductor manufacturing — but those jobs filled quickly, indicating that the workforce in the region has the knowledge and skills to meet the needs of Intel and other industry giants looking to expand. Ohio ranks among the top states to search for semiconductor manufacturing workers, filling jobs 18 percent faster than the rest of the country.

While Ohio is a relatively easy place to find workers to fill semiconductor manufacturing jobs, those jobs are still harder to fill than other jobs in the area. A semiconductor manufacturing job in Ohio takes 27 percent longer to fill than any other job in the state. Even the areas that are relatively poised to reshore jobs in critical supply chains will still need significant workforce development interventions and support.

Investing in Workforce Development

Addressing workforce challenges in critical supply chain sectors requires federal, state and local policymakers to collaborate with each other and work with education and training providers (workforce boards, schools, colleges and universities) to design curricula and innovate strategies that support the demands of regional labor markets. These efforts will require massive investment. Currently, the United States grossly underinvests in workforce development. The OECD reported in 2017 the United States spent only 0.1 percent of its GDP on active labor market policies (policies that improve job readiness, expand employment opportunities and enhance incentives to seek employment), a figure less than that of every other OECD country except for Mexico. Failing to invest in our critical supply chain workforce will present obstacles to reshoring efforts; however, there is a window of opportunity for regions to strategically build up their workforce and earn a competitive advantage in attracting reshoring firms.

Congress continues to look at the issues of workforce investment. The Bipartisan Innovation Act, which has moved to conference to enable final passage, brings together two innovative competitiveness bills from the House and Senate to invest in solutions that will expand access to opportunity for all our residents and stimulate more equitable outcomes including investments in apprenticeship, Pell grant flexibility and competitive grant funding to support long-term economic development goals in cities, towns and villages.

NLC continues to advocate for at-scale investments in workforce development and supports a $40 billion investment as laid out in the House-passed Build Back Better Act, as well as the reauthorization of the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act, which is currently under consideration in the House.