Public spaces play a vital role in the social and economic life and health of communities. Public spaces help build a sense of community, support physical and mental health, and bring business to local entrepreneurs. Unfortunately, access to public space, especially quality public space, is unequal across the country. New strategies are needed to reimagine public space that focus on centering the community.

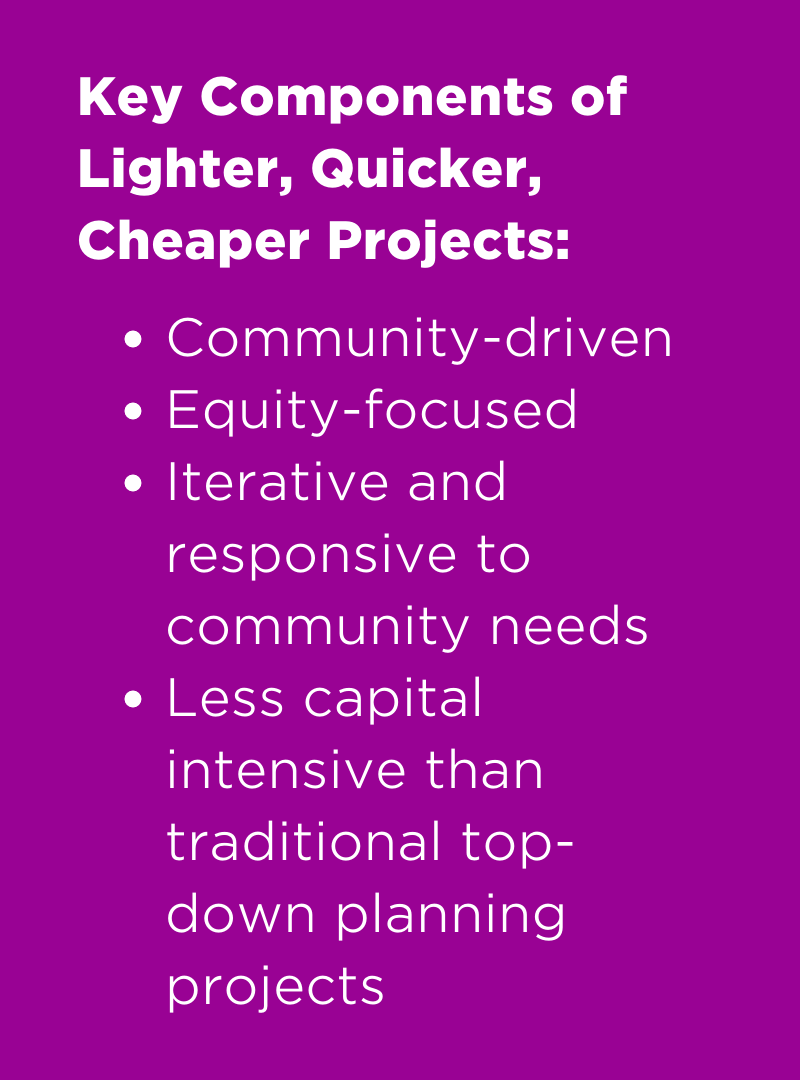

Lighter, Quicker, Cheaper (LQC) is a strategy to build quality public spaces from the bottom-up. LQC projects can include anything from installing planter boxes to implementing temporary street closures for outdoor dining and shopping or beautifying a neighborhood sidewalk. Although the possibilities are endless, these projects have a few attributes in common: they are light, they are quick and they are cheap.

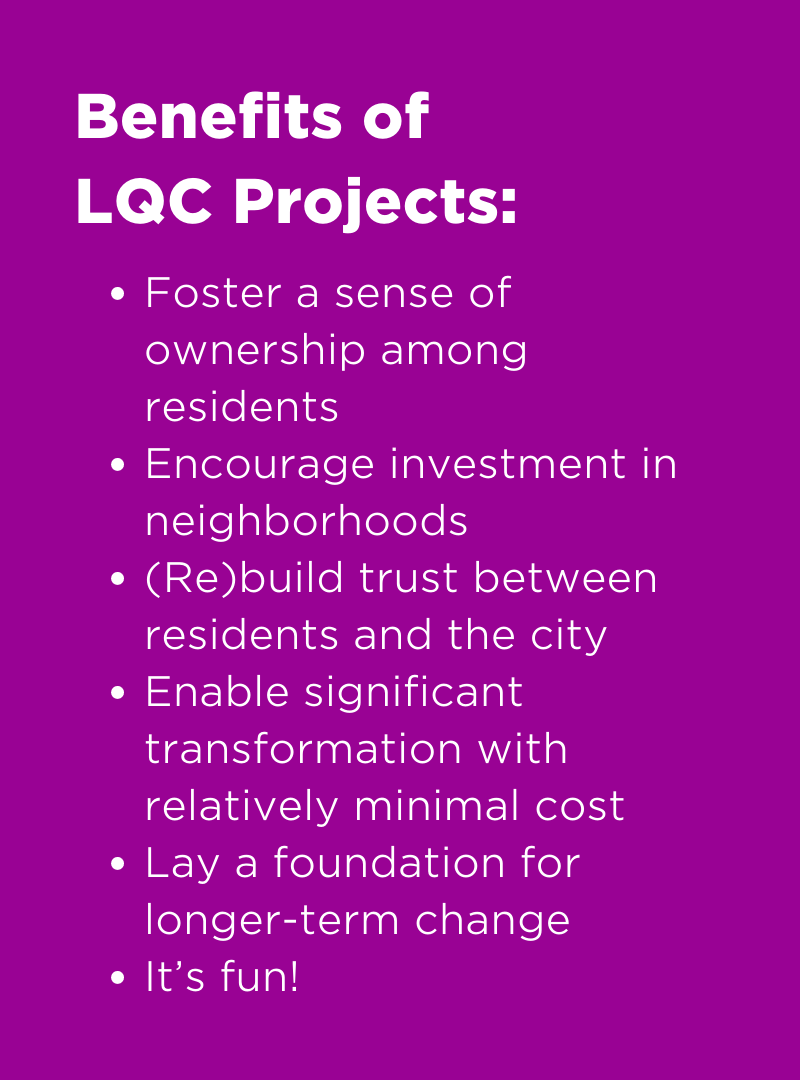

Implementing LQC projects allows cities to experiment and be flexible to adapt to changing needs over time. The interactive nature of LQC projects helps build, or in some cases, rebuild trust among stakeholders and pave the way for “tested” larger-scale capital investments. LQC provides a “low-cost, high-impact incremental framework” to improve access to public space that centers community voice.

Why Lighter, Quicker, Cheaper?

LQC projects can help cities address and rectify common pitfalls of reimagined public spaces: inequitable access to quality public spaces, and the fact that community members are often not involved in the planning or implementation of reimagined public spaces.

1. The pandemic highlighted the important role of public space — and also how inequitable access to quality public space is.

About 59 percent of White residents live within a ten-minute walk of a park or green space, compared to 61 percent of Black or Hispanic residents and 57 percent of Asian residents in U.S. cities with more than 75,000 residents, according to an analysis of a Trust for Public Land survey. Although these percentages do not convey a dramatic difference, there is more nuance to the story. Parks serving communities of color are, on average, half the size and five times more crowded than parks serving mostly White households.

2. There is a mismatch between what governments think residents want and what residents actually want.

The City of Oakland, CA, instituted a slow streets program in response to the pandemic, allowing residents to escape the confines of their homes while aligning with public health guidance. After consulting community members from East Oakland, a majority Black neighborhood with a history of disinvestment, the city found that East Oaklanders did not find the slow streets program useful for their needs. Instead of needing public space for recreation, they wanted public space to get to grocery stores, pharmacies and their jobs.

A Houston study similarly found that residents of different races/ethnicities and income levels were interested in different types of public space improvements. Higher-income and White residents were primarily concerned by connectivity, whereas Black and Latino/a residents were most interested in better-quality restrooms and lighting in parks due to the disparate quality of parks in their neighborhoods. Both cases echo a large body of research that highlights how people’s lived experiences require different public space needs.

Planning and implementing public space changes to better meet the needs of residents requires a grassroots approach. This is especially vital for residents who are low-income and for Black, Indigenous and other People of Color who continue to endure the legacy of top-down planning that has detrimental impacts on quality of life.

From large urban centers to small towns to rural communities, LQC projects are having widespread success across the U.S.

What Local Leaders Are Doing

Fergus Falls, MN: Population: 14,119

The City of Fergus Falls, MN, developed a Year of Play in 2018, an initiative to improve quality of life in the city by encouraging art and play in the community. The city followed an approach they called “lots of little,” where it supported many small projects led by different community groups instead of a few centralized, larger projects. The “lots” in Fergus Falls’ “lots of little” approach made it possible to invite more community members to be part of and contribute ideas to the overall initiative.

A community drag show coordinated by some of the city’s younger residents was one of Fergus Falls’ most successful projects. More than 100 residents attended the event, and it served as a safe space for LGBTQ+ community members to have fun and engage with the broader community.

Hartford, CT: Population: 121,054

The City of Hartford, CT, launched its Love Your Block program, funded by Cities of Service in 2019. Love Your Block Hartford was designed to increase neighborhood pride by creating opportunities for resident-led change through mini-grants for public space revitalization.

The city awarded a $1,000 mini-grant to a group of volunteers who wanted to revitalize a vacant lot in the heart of Hartford’s Latino/a community. The grant, along with $720 from cash and in-kind donations, allowed the neighborhood to install a basketball hoop, plant flowers, hold movie nights and create a space for a market. The lot, later deemed “the Art Box Lot,” flourished into a space for passive recreation and community events and improved feelings of safety in the neighborhood. The community-driven nature of the Art Box Lot was key to its success.

Memphis, TN: Population: 633,104

The City of Memphis, TN, launched its MEMFix program in 2010. The program aimed to reimagine Broad Avenue, a neglected commercial strip in the city’s downtown, in partnership with local business owners, residents and the nonprofit Livable Memphis.

With the help of local volunteers, Livable Memphis led an initial three-block streetscape exhibition, complete with protected bike lanes, pedestrian improvements, pop-up retail and festive programming. These changes ultimately led to an outpouring of investment into and transformation of Broad Avenue. MEMFix and MEMShop show how small, iterative changes can energize a space, stimulate longer-term investment and activate storefronts.

How Does LQC Support Local Goals?

The pandemic highlights the need for better access to public space. History highlights the need for a new approach to planning and governance that centers the community and those most in need. Local leaders have a responsibility to rectify past planning pitfalls and address the inequities the pandemic has exposed. LQC projects pave a better pathway forward for building quality public spaces that empower community members from the bottom up.

Learn More

For more information on how to reimagine public spaces, check out NLC’s Future of Cities Reimagining Public Space to Support Main Street Retail municipal action guide.