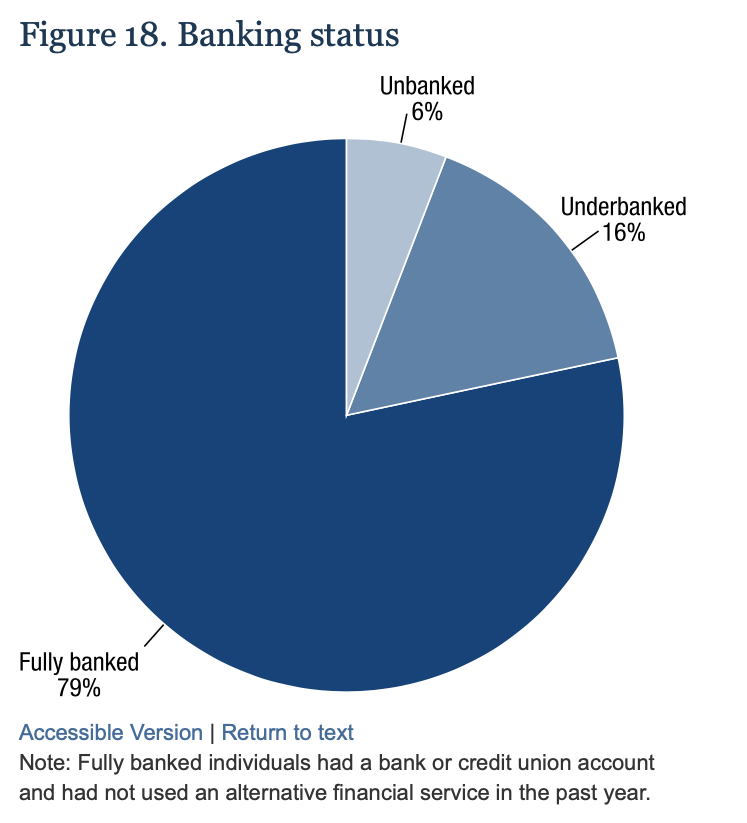

The U.S. Department of the Treasury recently released guidance explicitly allowing and encouraging direct-to-tenant payment as part of the disbursement of Emergency Rental Assistance (ERA) funds. Despite this move to increase access to funds for high-risk tenants and tenants whose landlords are unwilling to accept ERA funds directly, cities still face significant barriers reaching tenants who are “unbanked” and do not have an account at a banking institution, or are “underbanked” and may rely on alternative and often predatory financial service products such as check cashing services.

According to the 2019 Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation report, 7.1 million U.S. households (5.4 percent) do not have bank accounts. This is particularly prevalent in low-income households, households of color and for individuals with a disability. In 2019, 16.3 percent of Native American households, 13.8 percent of Black households and 12.2 percent of Hispanic households were unbanked, relative to 2.5 percent of white households. Similarly, 16.2 percent of working-aged disabled households are unbanked and roughly 37 percent of households with an income of less than $40,000 are either unbanked or underbanked.

BIPOC and low-income households are already vulnerable and disproportionately impacted by housing instability and economic inequality. Banking inequality exacerbates these conditions by blocking access to housing, jobs, insurance and other key opportunities. Supporting unbanked tenants now means helping vulnerable households weather the pandemic and set them up for success as we look to a more equitable post-COVID era.

Unbanked tenants face unique and significant burdens in simply applying for emergency rental assistance, along with difficulty accessing financial assistance if they do receive ERA funds. This includes challenges verifying their income, rent payments or the impact of COVID-19 on their financial situation when applying for rental assistance. Unbanked tenants may also face enormous challenges when attempting to cash direct-to-tenant rental assistance checks, such as astronomically high fees — which can be especially impactful for families who are already so vulnerable.

Here are five strategies cities should consider implementing to reach and serve unbanked tenants with financial assistance in both the short- and long-term:

1. Set Flexible Application Requirements for Assistance

Lengthy application processes and burdensome documentation requirements are major barriers to the swift dispersal of ERA funds, and often pose significant challenges for unbanked tenants in particular. Mayor Greg Fischer of Louisville, KY, whose rental assistance program has been highlighted by the Biden Administration as especially high-performing, partly attributes the city’s success in distributing funds to the fact that the Department of the Treasury allows renters to self-certify their income without extensive documentation. Louisville authorities have moved to accept just two pay stubs, or proxy documents from which prior cash income can be extrapolated, as acceptable documentation to receive ERA funds.

The Department of the Treasury has compiled numerous examples of acceptable self-attestation forms for tenants to verify employment, household income, loss of income or rental obligation, which can be adapted by cities for their individual needs.

Cities can also offer targeted support to tenants with the application process itself. The City of Chicago has strategically dedicated resources to assist vulnerable households in completing applications. By allowing applications to be submitted without all required documentation, the Department of Family and Support Services has the opportunity to step in once applications are selected for review and can then address documentation issues that unbanked tenants may face.

2. Partner with Local Institutions for No- or Low-Fee Cashing of Checks

Unbanked tenants may have to pay expensive fees in order to cash assistance checks before paying their landlord. For example, in metro Detroit, cashing in last year’s $1,400 federal stimulus check resulted in some tenants having to pay $60 to $100 in fees. To avoid having funds lost to fees as high as four to seven percent, ERA program administrators can include alternative means of assistance, such as by creating partnerships with check cashing facilities or local credit unions to reduce the transaction costs.

Some local businesses or institutions may already offer such services — for example, Kroger stores previously offered free cashing of government stimulus checks. When mailing direct-to-tenant assistance payments to residents, cities should include information about these partnerships and ways to take out cash without paying exorbitant fees.

3. Offer Alternative Methods of Payment

While cutting checks may be the most common method for distributing direct financial assistance, many cities are leveraging alternatives, such as distributing pre-paid debit cards.

In 2020, the City of Honolulu’s Office of Economic Revitalization issued $500 cash cards that could be spent at grocery stores and convenience stores. Funded by the CARES Act, the cards were mailed to roughly 6,000 households that participated in the City’s Household Hardship Relief Fund or other city-sponsored financial assistance programs. Portland, OR took a similar approach in partnering with the United Way of the Columbia-Willamette to provide debit cards covering $500 in household costs such as food, care, medicine, rent, utilities and transportation. Cities looking to pursue similar approaches should be mindful of agreement terms with card providers, including negotiating minimal overdraft and access fees.

The City of Los Angeles has taken this model one step further with its new Angeleno Connect Card program, which has enabled the distribution of approximately $36 million in assistance through more than 37,000 prepaid debit cards, ultimately helping more than 100,000 Los Angeles residents pay rent since the program began in March 2021. The prepaid debit Mastercards facilitate direct-to-tenant payments for the city’s ERAP program, along with other financial assistance initiatives, regardless of immigration status. Accelerator for America, a key partner to the Office of Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti in this work, will expand Los Angeles’ model to 10 additional cities.

Further leveraging technology for innovative methods of disbursement, the City of Chicago offered payment through PayPal or CashApp as alternatives to direct deposit for its COVID-19 Housing Assistance Grants.

4. Leverage a Range of Funding Streams to Provide Flexible Assistance

Recognizing that individual circumstances may preclude some households from accessing certain funds, cities should also seek to integrate a range of funding sources that can meet diverse needs and eligibility specifications.

Looking beyond federal and state funding, local nonprofit partners may be able to accommodate financial support needs that municipal programs cannot, depending on local or state regulations, or due to a household lacking certain documentation or banking access. Cities should leverage partnerships with such flexible nonprofits to distribute funds quickly, as well as provide aid to individuals who would otherwise be left unserved. Whether or not an individual has a bank account should be considered through intake processes and by local resource hotlines in order to connect individuals with the support services best suited to their needs.

Diverse funding streams and coordinated case management systems have been key for the Santa Clara County Homelessness Prevention System, as it has tapped into a network of 70 partner organizations to provide $36 million in aid to nearly 15,000 low-income households, including many that are unbanked, through a combination of direct financial assistance and rental assistance.

5. Connect Unbanked Tenants to Financial Empowerment Resources

In addition to supporting unbanked tenants in accessing emergency rental assistance funds, cities should use the opportunity to connect unbanked tenants with local financial empowerment resources and institutions.

This includes providing information about how tenants can establish a relationship with a banking institution. Cities should also look to facilitate a warm hand-off to any municipal financial education programs, leverage assistance payments to help residents create a checking account, and create relationships with financial service providers to minimize the barriers residents might face when they sign up for banking services (i.e. waiving fees or minimum balance requirements).

For example, the City of Little Rock, in partnership with Bank On Arkansas+, provided access to free checking accounts through bank partners for nearly 200 unbanked employees impacted by COVID-19, who previously received paper checks for their biweekly payments.

As cities continue to develop emergency rental assistance programs, scale financial support initiatives and refine distribution methods, it is important for them to maintain a focus on serving the most at-risk and hard-to-reach residents. Implementing payment processes or establishing supportive partnership agreements to increase access to emergency funds during this time of crisis will set cities up for success to support all of their residents — including those who are unbanked — more equitably and effectively long after the pandemic ends.

Become an NLC Member

Interested in more news like this? Join NLC and get access to timely resources, proven best practices, and connections to peer networks.