Executive Summary

Last spring, to mitigate the spread of COVID-19, schools across the country closed their doors and undertook the unprecedented task of delivering educational instruction remotely. In the weeks and months that followed, concerns about how well schools were able to make these transitions began highlight the inequities that many students faced. From food insecurity and homelessness to technology and income gaps, these often invisible inequities to the public became exacerbated by the pandemic.

IN THIS REPORT:

- Executive Summary

- Supporting Resource

- Partner Cities Map

- Listen In Audio

- Local Action Step Details

- Case Studies

Jump to a section in this report by clicking the corresponding link above.

Additionally, the significant number of students no longer attending school at all was a growing cause for concern. Fall 2020 enrollment data from the state of Michigan showed early signs that upwards of 53,200 students were unaccounted for. Similar concerns have persisted across the nation even as schools reopen for in-person instruction. This has major implications for lost instructional time that students may have experienced by not having access to the people and resources that they need to succeed.

Fall 2020 enrollment data from the state of Michigan showed early signs that upwards of 53,200 students were unaccounted for.

Michigan Public Schools

The “Student Reengagement After COVID-19 School Disruptions” project brought together thought leaders, practitioners and young people to identify and share information on promising developments to meet a rapidly changing reality.

Addressing Student Reengagement in the Time of COVID-19

All communities have a vested interest in student reengagement. Across the country, school and local leaders have reported steep declines in school enrollment and engagement since March 2020, with many students considered “missing” or “not contactable.”

From their collective efforts, a resource guide “Addressing Student Reengagement in the Time of COVID-19” was developed and described interim findings. It included the following four recommendations for local action steps:

- Convene stakeholders and highlight the issue of student disengagement prominently to direct resources toward relevant and effective reengagement strategies.

- Leverage resources such as community learning hubs to provide additional learning venue capacity.

- Support reengagement capacity and implementation through the redeployment or realignment of staff to facilitate more targeted outreach to disengaged students and connect them to supports and services; and

- Take steps in spring/summer 2021 with partners to prepare for a likely surge of student reengagement challenges as schools reopen and consider mounting an “Everyone Back to School” campaign.

Additionally, it highlighted several examples of local leadership reengaging students. Examples include The Colorado Youth for a Change partnership with Denver Public Schools and The City of Orlando’s Parramore Kidz Zone.

The YEF Institute based its approach to this project on extensive research findings indicating that when formal learning settings lose their connections with young people, the young person and the community alike face harmful long-term effects on earnings, employment, housing, and health that can last well into adulthood and put entire generations at risk. Building upon this evidence, the project identified several unique characteristics of pandemic-era reengagement challenges, all of which also warrant continuing attention:

- A lack of awareness at the national and local levels of the number of students who no longer engage or have lost contact with their schools;

- The spread of school disengagement to a wider range of middle and high school youth, requiring the development and application of targeted interventions;

- The need to add processes to ensure that affected young people who want to be heard help inform decisions about reengagement approaches; and

- The need for young people to have a broad set of supports and services, both inside and outside of school, to reengage effectively.

Given the continuing challenges of student disengagement and reengagement as the nation rebuilds from the pandemic, the National League of Cities and its partners remain committed to supporting city leaders and their partners to advance effective local strategies for student reengagement and will continue to identify and share effective strategies with our members and through existing networks.

Partner Cities Map

Listen in

Hear directly from students who lost contact with school after being impacted by COVID-19.

Digging Deeper

More Details on Recommended Local Action Steps

The scale of student reengagement challenges requires a collective, all-hands-on-deck response by municipal leaders, community organizations and schools. This section expands upon the rationales and nuances of four recommended local action steps.

Convene stakeholders and highlight the issue of student disengagement prominently to direct resources toward relevant and effective reengagement strategies.

The magnitude of the problem of locating the young people with whom schools have lost engagement is not yet fully known. Attendance figures are difficult to measure, as districts use different metrics to define students’ presence in different learning settings (virtual, hybrid, in-person) and implementation of academic instruction has varied.

Regardless of the national scale of the crisis, the solutions and strategies need to be designed with local context in mind, including COVID-19 public health protocol, culturally appropriate interventions and community engagement.

Given the time-sensitive crisis and compounding inequities that far too many young people in middle and high school may be facing, we recommend that municipal leaders act decisively and work collaboratively with school district officials to convene various community stakeholders who have built trusting relationships with community members to call attention to the crisis and respond appropriately.

One of the most important elements of the “Student Reengagement After COVID-19 School Disruptions” project has been the conversations centered around the experience of young people impacted by the pandemic, particularly middle and high school youth who at one point or another lost touch with their school. Through one-on-one discussions, focus group conversations and town-halls hosted in partnership with the Institute for Educational Leadership’s youth-led Next Generational Coalition, these young people spoke their truth to power, sharing what they need to reengage in school.

It is critical that efforts to convene stakeholders include young people. Our learnings indicate the need to uplift the voices of those most closely impacted, identify key strategies for reengagement, and enable the forging of genuine youth-adult partnerships that make space for young people to develop and hone their own power.

Additional stakeholders may include family and community members, school district leaders and educators, nonprofit partners, businesses, postsecondary institutions, and city agencies. Existing COVID-19 response task forces, working groups, or conveners may be leveraged to help identify and share local data of student attendance among stakeholders to define the local context and inform outreach.

Coordinated partnerships can help define existing resources, including staffing, funding, and relationships with community members, to quickly locate and reengage middle and high school students who are chronically absent or disengaged.

Leverage resources such as community learning hubs to provide additional learning venue capacity.

For many middle and high school students, particularly low-income students and students of color, pandemic-related disruptions have presented a number of challenges in accessing educational opportunities and continuing their engagement with school. Young people’s testimonials recount facing:

- Hardships attaining the technology and internet needed to connect to school;

- Difficulty navigating online learning and familiarizing themselves with digital tools;

- Increased responsibilities as caretakers of younger siblings, children, and other household members;

- Feelings of isolation and difficulty concentrating due to competing priorities at home, which sometimes includes full- or part-time employment.

As schools across the country begin phased reopening, they will need to first address pre-existing infrastructure and transportation challenges, such as ventilation, plumbing, overcrowding, and pupil transportation. To maximize in-person instruction and engagement, the use of additional community facilities can help leverage supports, services, and instruction to reengage small cohorts of middle and high school youth.

Many municipal leaders across the country have taken significant steps to support the coordination and implementation of community learning hubs. Hundreds of communities across the country have transformed community and city facilities such as recreation centers, libraries, museums, houses of worship, and other underutilized facilities to serve as remote learning spaces for students during the pandemic, providing technology, broadband access, adult supervision, enrichment activities and food/nutrition.

Successful learning hubs should be constructed in partnership with school district leaders and administrators to ensure equitable and effective implementation.

Learn more about how your municipality can implement and support community learning hubs.

Support reengagement capacity and implementation through the redeployment or realignment of staff to facilitate more targeted outreach to disengaged students and connect them to supports and services.

Many school educators, including paraprofessionals, counselors, and principals, are restructuring their days to conduct personal outreach to students who are chronically absent or disengaged, through phone calls, emails, and door-knocking. Yet, as schools continue to reopen for in-person instruction, school educators cannot conduct outreach alone.

Practice shows that direct outreach can take many forms in addition to contact by school employees, including partnerships with government and community agencies to reach out to families, as well as peer-to-peer initiatives. Such outreach often reveals that disconnection with school is a symptom of other issues facing the family, such as food and income insecurity, illness, extra student responsibilities, or lack of internet connectivity. The most effective approaches work to address these issues as part of returning the student to school.

Municipalities can call on community partners such as local re-engagement centers – organizations that conduct active outreach to encourage youth who are disconnected and disengaged to return to school – to work in partnership with their school districts to redeploy staffing and resources to reengage middle and high school students after COVID-19 disruptions.

Various communities across the country, such as Colorado Youth for a Change (featured example), employ AmeriCorps members to help school districts reconnect with students and establish enrichment activities that foster a sense of belonging while addressing basic needs insecurities.

Take steps in spring/summer 2021 with partners to prepare for a likely surge of student reengagement challenges as schools reopen and consider mobilizing an “Everyone Back to School” campaign.

COVID-19 has uncovered and exacerbated existing inequities and inadequacies across a range of social structures and our nation’s education system is not immune.

While we continue to learn more about the impact of COVID-19 on young people, early red flags show a need for short-term responses and long-term preparation to respond to the growing needs of students who have lost contact with school during the pandemic. Of particular concern is the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on middle and high school students of color, students from low-income backgrounds, students with disabilities, English language learners, students who are migratory, students experiencing homelessness, students in correctional facilities, and students in foster care.

To respond, municipalities can work with school districts and community-based organizations to establish supports and services that address the academic and social and emotional learning needs of students.

Key considerations:

- Establish a city/schools “Everyone Back to Schools” campaign.

Regardless of the plans for Summer 2021 or the 2021-2022 academic school year, municipal leaders, school district leaders, and community partners can design and implement an “Everyone Back to School” campaign that calls attention to the crisis. Particular attention should be given to communications and marketing strategies that reflect the local context, including language, demographic, and cultural differences.

- Address lost instructional time using

Traditional classroom-based summer schools have not been shown effective in reconnecting students who have become disengaged or disconnected with school. Fortunately, there are many models that do work, including college and career readiness programs, tutoring support, and expanded learning opportunities in the community. Municipal leaders and community organizations are well positioned to provide such programming during afterschool and summer.

- Build upon local strategies such as Summer Youth Employment that already involve significant numbers of young people.

These programs, when used effectively, can prepare youth and young adults in low-income communities for careers through career exploration, adult mentorship, work readiness preparation and skills training, and improved economic opportunity through subsidized job placements. Establishing connections with youth through these programs can help reengage students in formal learning environments, particularly supporting students who lost contact with school due to employment.

- Address emerging concerns among communities of color about school safety.

Several young people who participated in this work expressed facing mental health and wellness challenges related to the pandemic and subsequent crises, including concerns over school safety. Municipal leaders, school district leaders, and community partners can step in to establish programs and services that support mental health and wellness, help navigate an overwhelmed and overburdened public system, and engage youth as key leaders and strategists.

Case Studies

Local examples of student reengagement

Colorado Youth for a Change

Across the state of Colorado, early attendance data showed drops in enrollment both in districts that started the school year online and in those that had instruction in school buildings. To mitigate lost instructional time and address student well-being, Governor Jared Polis made investments to expand AmeriCorps programs.

Thanks in part to the funding from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, the Governor’s office, and local philanthropy, 23 AmeriCorps members were redeployed while an additional 11 were added to Colorado Youth for a Change’s (CYC) Corps for Change Program to form a CYC Corps to support student engagement and reengagement. While their reach can be felt across the state, redeployment efforts concentrated in the City of Denver to support Denver Public Schools (DPS).

Through a partnership with Colorado Youth for a Change (CYC), Serve Colorado, the Governor’s Office, and AmeriCorps members are making phone calls and home visits, supporting in-class instructions, and connecting students and families to basic needs resources and supports.

AmeriCorps members receive training and monthly supervision though CYC and utilize a site supervisor model so that members work in tandem with district leaders to re-engage students in school.

Redeployment during the pandemic to focus on the recent school disengagement population is built upon a dropout reengagement effort underway for fifteen years. “While our traditional CYC Reengagement program tracks the numbers called, reenrolled, and retained over the year, we’ve had to track data differently through this AmeriCorps expansion,” says CYC Development Director Julia Hughes. “Service sites can look very different across districts and schools, as each community has been able to leverage its AmeriCorps members to meet local needs and fill gaps within that community. Over 3,000 students have been served by [the program] in the 2020-2021 school year.” In Denver Public Schools alone, the CYC reengagement program served 249 students and re-enrolled 123 who had been disconnected with school, 82 percent of whom are still enrolled or have graduated.

To do this, CYC AmeriCorps members coordinate with school districts and municipal leaders to conduct direct outreach to middle and high school students who are chronically absent as well as provide academic and enrichment activities.

Through their outreach, CYC AmeriCorps members aim to reestablish a connection with students, address basic needs insecurities through case management and community resources, and provide ongoing programming and check-ins that support positive youth development. CYC AmeriCorps members recognize that strong partnerships with school districts have been essential in keeping students connected and engaged. They strengthen these connections through continued communication with school administrators and educators, share periodic updates on youth well-being, and offer additional supports.

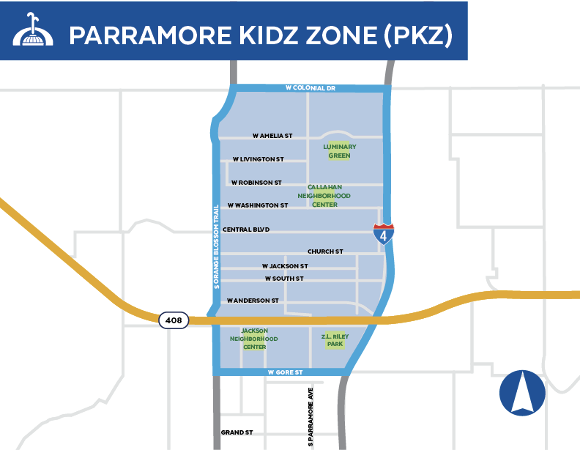

Parramore Kidz Zone

The City of Orlando and the Orange County Public Schools are working together to find and reengage “missing” students and keep young people in the Parramore Kidz Zone (PKZ) neighborhood involved in school and social activities during the pandemic.

“Remote learning has put a strain on families and students alike, says PKZ Academic Coordinator Dr. Patricia Reba. “We found that many were home with little supervision, and not logging in to complete schoolwork. We began conducting home visits when schools first shut down and continued throughout the summer and the new school year.”

School principals notify PMZ student advocates when a student is absent from online or in-person classes, and the advocates visit the student to check on them to see what has caused the absence and to get them re-engaged. “We go find them if they don’t log on,” says Orlando’s Children and Education Manager Brenda March.

Using a “whatever it takes” approach, city staff do wellness check-ins and student questionnaires to determine family needs, and distribute food, laptop computers, and other essentials, as well as providing mental health webinars and social-emotional kits when needs are found. Cash assistance is available to families whose children are enrolled in PKZ programming and in school. Staff reconfigured community facilities to provide centers for remote learning and conducted school check-ins for those who are struggling at school in Orlando’s hybrid model. A counselor, academic helpers, and volunteer mentors are available, as well.

The PKZ team credits the more than two decades of investment for their ability to revamp, redirect, and redeploy staff and resources swiftly throughout the pandemic. It is the ecosystem approach that allowed them to leverage existing partnerships, especially those with the school district, to support middle and high school youth in the PKZ and beyond. “Our partnership with the school district was invaluable in supporting our students,” says Dr. Reba.

These partnerships and authentic collaboration allowed the Orlando team to pursue competitive grants from various local philanthropies and national organizations. They also received funding from the City of Orlando, the Florida Department of Education’s Ounce of Prevention program, and the Department of Health.

While recounting the suffering that many families in the PKZ experienced, Dr. Reba shared that through their ongoing engagement and reengagement efforts amid the pandemic, 80% of their high school population has returned to in-person school instruction and 30 students are completing their academic year online. So far, they haven’t lost a student.

As the 2020-2021 school year continues, they are keeping kids engaged outside of school as well, with socially distanced outdoor activities throughout the year, and preparations for a youth employment program to keep young people busy and productive during the summer.

Early signs show the approach seems to be working. Five high school seniors in the program have been accepted by multiple colleges, and advocates report most of their students are staying fully engaged in school.

Support and Partners

This report is brought you by support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Annie E. Casey Foundation. The National League of Cities partnered with the Coalition for Community Schools, housed within the Institute for Educational Leadership, to provide support and information for city leaders and their partners.