In Charleston, WV, the city approved a $98.9 million budget in fiscal year 2019 but is on track to end with a $2 million deficit. The city of Boulder, CO, projects a shortfall of approximately $21 million in the general fund and a $41 million overall budget deficit. In New Orleans, LA, city officials estimate the city could lose up to $150 million this year as a result of losses in sales tax revenue.

Despite significant uncertainty about how long the coronavirus and the economic impacts of the public health crisis will last, one thing that is clear is that the U.S. has entered a recession. From skyrocketing unemployment, jobless claims and business closures to plummeting consumer spending and income, families and businesses, particularly Americans of color, are burdened with mounting financial insecurity. As local leaders scramble to help their communities face these new economic realities, they are also working to soften the blow to their own budgets.

To better understand the depths and contours of the fiscal impacts on cities, towns and villages nationwide, we analyzed finance data from the U.S. Census Bureau and unemployment projections from the Congressional Budget Office. We find that a 1 percentage point increase in unemployment results in a 3.02% budget shortfall for cities, towns and villages.

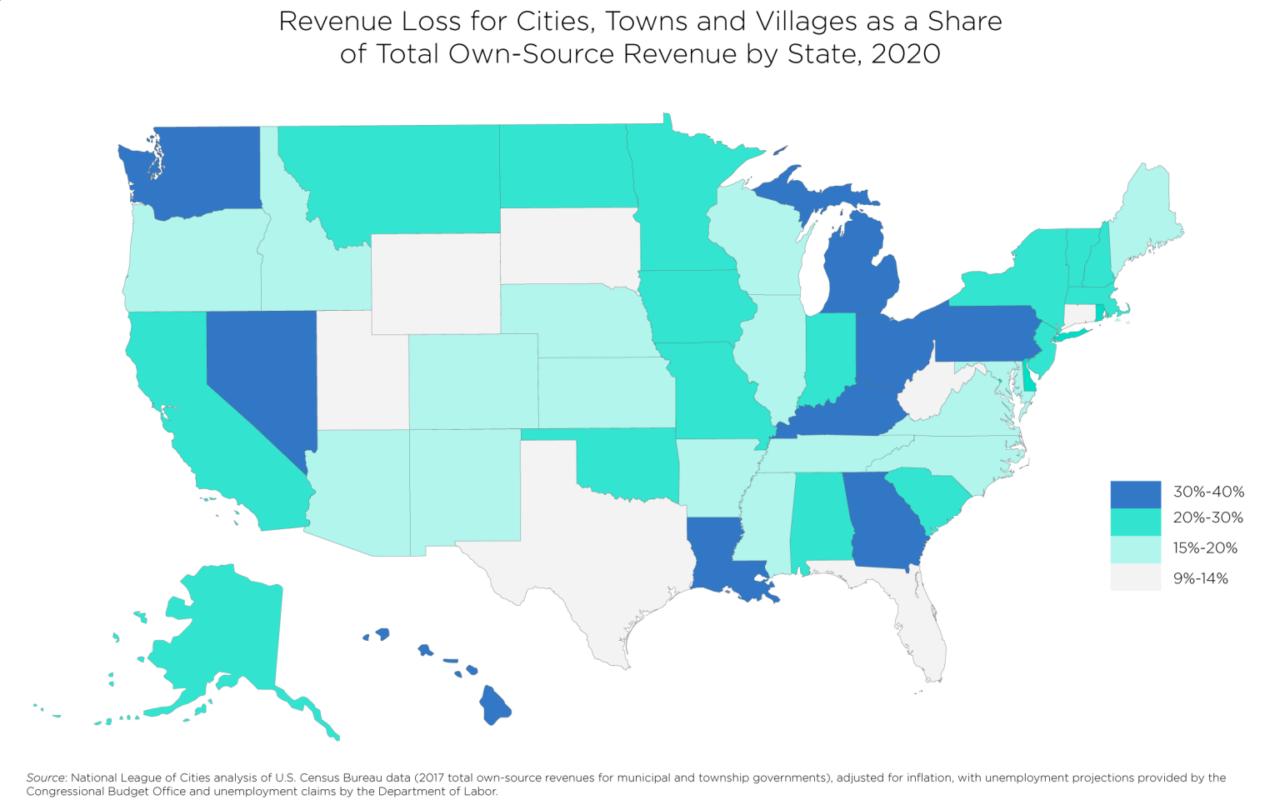

Collectively, this amounts to over $360 billion in lost revenues between 2020 and 2022, with shortfalls varying significantly by state.

Measuring Budget Shortfalls

Our analysis is rooted in the proven relationship between how local governments raise revenues and how these revenues rise and fall with economic conditions. For example, cities that generate the majority of their revenue from sales or income taxes have been hit hard as their budgets experience the immediate impacts of massive declines in jobs and consumer spending. For example, the city of Akron, Ohio, which is highly dependent on the income tax announced in March that it is furloughing one-third of its municipal workforce due to budget shortfalls.

Property tax revenues, and even fees and charges, tend to be less responsive to economic conditions generally. However, rising unemployment is dampening real-estate demand and accelerating foreclosures and missed tax payments, leading even property tax-dependent cities and those depending on fees and charges to feel the fiscal gravity of the downturn. The city of Richardson, TX’s $18 million shortfall this year is attributed primarily to a decline in fees and permits resulting from a lull in construction, low hotel occupancy rates, inability of residents to pay water and sewer fees, reductions in commercial solid waste service requests, and the closing of a municipal recreation center.

Based on these relationships, we project that the portion of revenues for cities, towns and villages generated by sales and income taxes will have the largest relative fiscal impact on budget shortfalls, followed by revenues generated by fees and charges then property tax revenues. Since the share of local revenue generated by each stream varies greatly by state, so too does the sensitivity of local budgets to economic conditions. As a result, cities, towns and villages in Alabama, which rely primarily on sales tax revenue, have the most responsive fiscal structure to economic downturns, while those in Maine, relying primarily on property tax revenues, have the least.

Shortfalls Massive, Yet Uneven

Budget shortfalls are the result not only of fiscal structure but also the underlying economic conditions driving the ebb and flow of these various revenue sources. Although the pandemic has forced the shutdown of the entire economy, unemployment and other economic impacts have not been evenly distributed. The Bureau of Labor Statistics jobs report revealed that nearly half the leisure and hospitality jobs were lost in April 2020. Local economies with a large share of these jobs, as well as jobs in other vulnerable industries like transportation, services, and travel, will feel the sting of unemployment more so than communities with smaller shares of these jobs.

Our estimates account for these variations in new sources of unemployment by integrating “additional unemployment,” or the amount of unemployment above pre-pandemic levels for 2020, 2021 and 2022 based on projections by the Congressional Budget Office and unemployment claims by state from the Department of Labor.

Marrying local revenue responsiveness with the level of elevated unemployment rates provides a more complete picture of budget shortfalls for cities, towns and villages nationwide, as well as shortfall variations across the states. Collectively, our model estimates a 3.02% budget shortfall for each 1 percentage point increase in unemployment. With additional unemployment 7.2 percentage points above pre-pandemic levels, cities will face a shortfall of over $134 billion for 2020 alone, representing 21.6% of total own-source revenue. Extended out to 2022, cities, towns and villages can expect losses amounting to over $360 billion.

By state, revenue losses for cities, towns and villages in 2020 is expected to be the most significant in Pennsylvania, with a shortfall representing 40.2% of revenues. Connecticut will experience the least significant shortfall, at 9.3% of total own-source revenue.

These two states demonstrate key elements of our fiscal impact model. Pennsylvania is projected to have 11.59 percentage points more unemployment this year than expected before the pandemic struck, with a fiscal structure that amounts to revenue losses at 3.30% per 1 percentage point increase in unemployment. Cities, towns and villages in Connecticut, on the other hand, are only anticipating 3.86 percentage point increase in unemployment over its pre-pandemic baseline, with a revenue responsiveness rate of 2.30% per 1 percentage point increase in the unemployment rate.

Shortfalls Have Real Consequences

If local governments are left in a position to go-it-alone, the economic implications will be disastrous. With significant restrictions on raising new revenues, cities are turning to their options of last resort, which are to severely cut services at a time when communities need them most, to layoff and furlough employees, who comprise a large share of America’s middle class, and to pull back on capital projects, further impacting local employment, business contracts and overall investment in the economy. These cuts will also exacerbate infrastructure challenges, which will place future fiscal burden on local, state, and federal government.

With states likely to cut aid to local governments to help alleviate their own budget pressures, federal support for cities, towns and villages is more critical than ever. Without it, nearly 1 million municipal workers could be furloughed or laid off, resulting in fewer police officers to respond when residents call 9-1-1, fewer firefighters to rush to the scene, fewer EMS responders to help those in need, fewer sanitation workers to keep communities clean, and fewer services for youth, seniors, and the most vulnerable people in our communities. Federal relief for local governments who have been on the frontlines of this crisis is critical to ensuring that families and workers in our communities will be safer, healthier and more prosperous, and that our national economy is resilient in the face of this unprecedented, pandemic-induced recession.